| T O P I C R E V I E W |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 12/08/2013 : 15:18:12

Firebyrd -- GENE CLARK

for the best book on Gene-John Einarson's Gene Clark biography is the best. A heartbreaking & brilliant portrait of Gene.

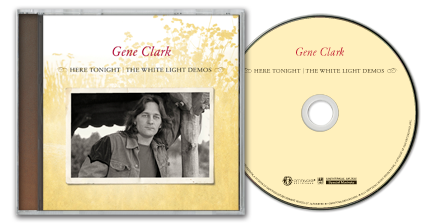

WHITE LIGHT (from the newly released Here Tonight:White Light Demos)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guVJ7QJyV3Q

Be sure to get the White Light Demos--a must for Gene fans!!

Byrds bass player Chris Hillman stressed not only Clark's songwriting skill, but also his onstage charisma: "People don't give enough credit to Gene Clark. He came up with the most incredible lyrics. I don't think I appreciated Gene Clark as a songwriter until the last two years. He was awesome! He was heads above us! Roger wrote some great songs then, but Gene was coming up with lyrics that were way beyond what he was. He wasn't a well-read man in that sense, but he would come up with these beautiful phrases. A very poetic man--very, very productive. He would write two or three great songs a week". "He was the songwriter. He had the "gift" that none of the rest of us had developed yet.... What deep inner part of his soul conjured up songs like "Set You Free This Time,"

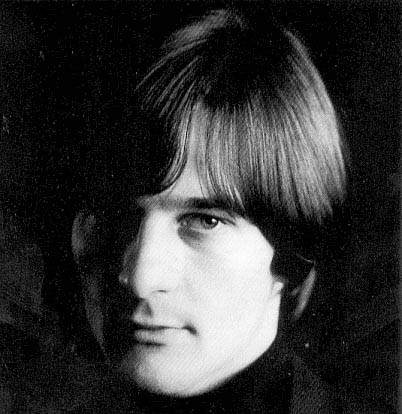

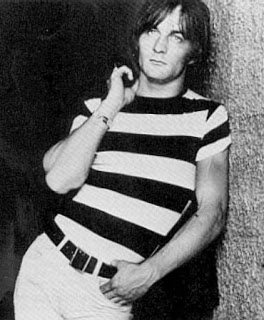

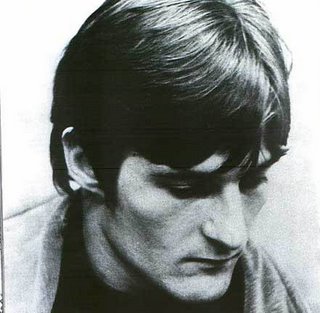

Harold Eugene Clark (November 17, 1944[1] – May 24, 1991), known professionally as Gene Clark, was an American singer-songwriter and founding member of the folk rock band The Byrds. Clark was The Byrds' dominant songwriter between 1964 and early 1966, penning most of the band's best-known originals from this period, including "I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better", "She Don't Care About Time", "Set You Free This Time", and "Eight Miles High". He created a large catalogue of music in several genres, but failed to achieve solo commercial success. Clark was one of the earliest exponents of psychedelic rock, baroque pop, newgrass, country rock and alternative country.

Gene Clark was born in Tipton, Missouri, the third of thirteen children in a family of Irish, German and Native American heritage. His family moved to Kansas City where he began learning the guitar and harmonica from his father at a young age. He was soon playing Hank Williams tunes as well as material by early rockers such as Elvis Presley and the Everly Brothers. He began writing his own songs at age 11. By the time he was 15 he had developed a rich tenor voice and he formed a local rock and roll combo, Joe Meyers and the Sharks. Like many of his generation, Clark developed an interest in folk music because of the popularity of the Kingston Trio. When he graduated from Bonner Springs High School in Bonner Springs, Kansas in 1962, Clark formed a folk group, the Rum Runners.

Formation of The Byrds

Clark was invited to join an established regional folk group, the Surf Riders working out of Kansas City at the Castaways Lounge, owned by Hal Harbaum. On August 12, 1963, he was performing with them when he was discovered by The New Christy Minstrels. They hired him for their ensemble and he recorded two albums with them before leaving in early 1964. After hearing the Beatles, Clark quit the Christys and moved to Los Angeles where he met fellow folkie/Beatles convert Jim (later Roger) McGuinn at the Troubadour Club. In early 1964 they began to assemble a band that would become The Byrds.

Gene Clark wrote or co-wrote many of The Byrds' best-known originals from their first three albums, including: "I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better", "Set You Free This Time", "Here Without You", "You Won't Have to Cry", "If You're Gone", "The World Turns All Around Her", "She Don't Care About Time" and "Eight Miles High". He and McGuinn also composed "You Showed Me", which was recorded but not released by the Byrds, and became a hit for the Turtles when they recorded it in 1969. He initially played rhythm guitar in the band, but relinguished it to David Crosby and became the Byrd's tambourine and harmonica player. Bassist Chris Hillman noted years later in various interviews remembering Gene: "At one time, he was the power in the Byrds, not McGuinn, not Crosby—it was Gene who would burst through the stage curtain banging on a tambourine, coming on like a young Prince Valiant. A hero, our savior. Few in the audience could take their eyes off this presence. He was the songwriter. He had the "gift" that none of the rest of us had developed yet.... What deep inner part of his soul conjured up songs like "Set You Free This Time," "I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better," "I'm Feelin' Higher," "Eight Miles High"? So many great songs! We learned a lot of songwriting from him and in the process learned a little bit about ourselves."

A management decision delivered the lead vocal duties to McGuinn for their major singles and Bob Dylan songs. This disappointment, combined with Clark's dislike of traveling (including a chronic fear of flying) and resentment by other band members about the extra income he derived from his songwriting, led to internal squabbling and he left the group in early 1966. He briefly returned to Kansas City before moving back to Los Angeles to form Gene Clark & the Group with Chip Douglas, Joel Larson, and Bill Rhinehart.

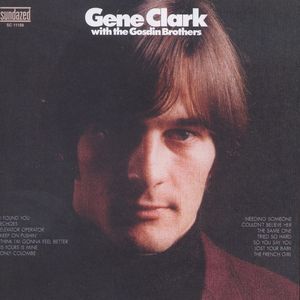

Solo career, rejoining The Byrds and Dillard & Clark

Columbia Records (The Byrds' record label) signed Clark as a solo artist and, in 1967, he released his first solo LP, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers. The Gosdin Brothers were selected to back Gene because they shared manager Jim Dickson, and Chris Hillman, who played bass on the album, had worked with the Gosdin Brothers in the mid-1960s when he and they were members of the Southern California bluegrass band called The Hillmen. The album was a unique mixture of pop, country rock and baroque-psychedelic tracks. It received favorable reviews but unfortunately for Clark, it was released almost simultaneously with the Byrds' Younger Than Yesterday, also on Columbia, and (partly due to his 18 month-long public absence) was a commercial failure.

With the future of his solo career in doubt, Clark briefly rejoined The Byrds in October 1967, as a replacement for the recently departed David Crosby, but left after only three weeks, following an anxiety attack in Minneapolis. During this brief period with The Byrds, he appeared with the band on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, miming to the group's current single "Goin' Back", as well as to "Mr. Spaceman". Although there is some disagreement among the band's biographers, Clark is generally viewed as having contributed background vocals to the songs "Goin' Back" and "Space Odyssey" from the then forthcoming Byrds' album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, as well as being an uncredited co-author, with Roger McGuinn, of "Get to You" from that album.

In 1968, Clark signed with A&M Records and began a collaboration with banjo player Doug Dillard. With guitarist Bernie Leadon (later with The Flying Burrito Brothers and the Eagles), they produced two country rock and bluegrass-flavored albums: The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark and Through the Morning Through the Night, both of which fared poorly on the charts. Through the Morning, Through the Night was more bluegrass in character than its predecessor, used electric instrumentation and included Donna Washburn (Dillard's girlfriend) as a backing vocalist, all of which contributed to the departure of Leadon. The loss of Leadon as a co-writer meant that the album featured more covers than originals, and the change of musical direction caused Clark to lose faith in the group, which disbanded in late 1969. Today, Dillard & Clark are viewed as pioneers of country rock.

The Dillard & Clark song "Through The Morning Through The Night" was used in Quincy Jones's soundtrack of the 1972 Sam Peckinpah movie The Getaway. This song, along with "Polly" (both from the second Dillard and Clark album), was also recently covered by Robert Plant and Alison Krauss on their album Raising Sand.[citation needed]

In 1970, Clark began work on a new single, recording two tracks with the original members of the Byrds (each recording his part separately). The resulting songs, "She's the Kind of Girl" and "One in a Hundred", were not released at the time due to legal problems and were included later on Roadmaster. Frustrated with the music industry, Clark bought a home at Albion near Mendocino, married, and fathered two children while living off his still substantial Byrds royalties.

In 1970 and 1971, Clark contributed vocals and two compositions ("Tried So Hard" and "Here Tonight") to albums by the Flying Burrito Brothers.

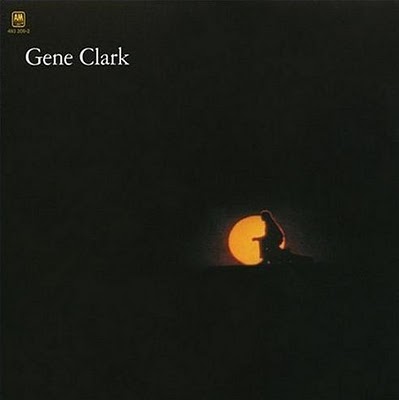

White Light

It wasn't until 1971 that another Gene Clark solo set finally emerged. The album was titled White Light, although the fact that the name was not included on the cover sleeve led some later reviewers to assume mistakenly that it was titled 'Gene Clark'. The record was produced by the much sought after Native American guitarist Jesse Ed Davis with whom Clark developed great rapport, partly due to their common Indian ancestry. A largely acoustic work supplemented by Davis' slide guitar work, the album contained many introspective tracks such as "With Tomorrow", "Because of You", "Where My Love Lies Asleep" and "For a Spanish Guitar" (supposedly hailed by Bob Dylan as a song he would have been proud to compose). All of the material was written by Clark, with the exception of the Dylan and Richard Manuel composition, "Tears of Rage". Launched to considerable critical acclaim, the LP failed to gain commercial success, except in the Netherlands where it was also voted album of the year by rock music critics. Once more, Clark's refusal to undertake promotional touring adversely affected sales.

In the spring of 1971, Clark was commissioned by Dennis Hopper to contribute the tracks "American Dreamer" and "Outlaw Song" to Hopper's film project American Dreamer. A re-recorded, longer version of the song "American Dreamer" was later used in the 1977 film The Farmer, along with an instrumental version of the same song plus "Outside the Law (The Outlaw)" (a re-recording of "Outlaw Song").

In 1972, Clark assembled a backing group consisting of highly accomplished country rock musicians to accompany him on an album with A&M. Progress was slow and expensive and A&M terminated the project before completion. The resulting eight tracks, together with those recorded with The Byrds in 1970/71 and another with The Flying Burrito Brothers ("Here Tonight"), were belatedly released as Roadmaster in the Netherlands only.

Byrds

Clark then left A&M to join the reunion of the original five Byrds and cut the album Byrds (released in 1973) which charted well (US # 20). Clark's compositions "Full Circle" and "Changing Heart" plus the Neil Young covers on which he did the lead vocal work ("See the Sky About to Rain" and "Cowgirl in the Sand") were widely regarded as the standout tracks on a record which received some negative critical response. Disheartened by the bad reviews and unhappy with David Crosby's performance as the record's producer, the group members chose to dissolve The Byrds. Clark briefly joined McGuinn's solo group, with which he premiered "Silver Raven", arguably his most celebrated post-Byrds song.

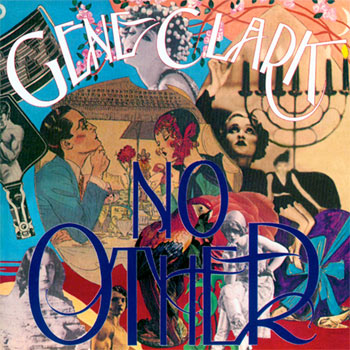

No Other

On the basis of the quality of Clark's Byrds contributions, David Geffen signed him to Asylum Records in early 1974. Asylum was the home of the most prominent exponents of the singer-songwriter movement of the era and carried the kind of hip cachet that Clark hadn't experienced since his days with The Byrds. He retired to Mendocino and spent long periods at the picture window of a friend's cliff-top home with a notebook and acoustic guitar in hand, staring at the Pacific Ocean. Deeply affected by his visions, he composed numerous songs which would serve as the basis for his only Asylum LP, the aptly titled No Other. Produced by Thomas Jefferson Kaye with a vast array of session musicians and backing singers, the album was an amalgam of country rock, folk, gospel, soul and choral music with poetic, mystical lyrics. Critics reviewed the album favorably but the fact that No Other wasn't a conventional pop/rock opus meant diminished public appeal. Furthermore, its production costs of $100,000 which yielded only eight tracks prompted Geffen to berate Clark and Kaye. The album was minimally promoted and stalled in the charts at No. 144. Moreover, the singer's return to Los Angeles and his reversion to a hedonistic lifestyle resulted in the disintegration of his marriage. In spite of these setbacks, he mounted his first solo tour (by road), playing colleges and clubs with backing group, the Silverados.

Two Sides to Every Story

Throughout 1975 and 1976, Clark hinted to the press that he was assembling a set of "cosmic Motown" songs fusing country-rock with R&B and funk, elaborating on the soundscapes of No Other. A set of ten demos were submitted to RSO Records, who promptly bought out Clark's Asylum contract.

In 1977, Clark released his RSO Records debut entitled Two Sides to Every Story. Once again, Thomas Jefferson Kaye produced it, but with a much more understated hand. The album was another characteristic offering of his style of sensitive country-rock balladry and it failed to achieve US chart success. In a belated attempt to find an appreciative public, he temporarily overcame his travel anxiety and launched an international promotional tour.

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman

For his British tour dates, Clark found himself on the same bill as ex-Byrds Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman. The three signed with Capitol Records which released their self-titled debut in 1979. McGuinn, Clark & Hillman was a rebirth in both performing and songwriting for Clark. McGuinn's "Don't You Write Her Off" reached No. 33 in April 1979. Many felt that the album's slick production and disco rhythms didn't flatter the group, and the album had mixed success both critically and commercially, but it sold enough to generate a follow up. McGuinn, Clark and Hillman's second release was to have been a full group effort entitled City, but a combination of Clark's unreliability and his dissatisfaction with their musical direction (mostly regarding Ron and Howard Albert's production) resulted in the billing change on City to "Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, featuring Gene Clark". Despite the turmoil, Clark penned a classic love song, "Won't Let You Down", rumoured to have been offered as an olive branch to the other former Byrds. By 1981, Clark had left, and the group recorded one more album as "McGuinn/Hillman".

Rehabilitation, Firebyrd, and So Rebellious a Lover

Clark moved to Hawaii with Jesse Ed Davis to try to overcome his drug dependency, remaining there until the end of 1981. Upon his return to L.A., he assembled a new band and proceeded to record what would eventually become the album Firebyrd (the title acknowledges the Byrds and Firefall origins of some members). While waiting for Firebyrd to be released, Clark joined up with Chris Hillman and others in an abortive venture called Flyte which failed to secure a recording contract and was quickly dissolved. Firebyrd's eventual release in 1984 coincided with the emergence of jangle rockers like R.E.M. and Tom Petty who had sparked a new interest in the Byrds. Clark began developing new fans among L.A.'s roots-conscious Paisley Underground scene. Later in the decade, he embraced his new status by appearing as a guest with The Long Ryders and by cutting an acclaimed duo album with Carla Olson of the Textones titled So Rebellious a Lover in 1986, which was produced and arranged by noted session drummer, Michael Huey

Later career, illness and death

In 1985 Clark approached McGuinn, Crosby, and Hillman 1984 regarding a reformation of The Byrds in time for the 20th anniversary of the release of "Mr. Tambourine Man". The three of them showed no interest. Clark decided to assemble a "superstar" collection of musicians, including ex-Flying Burrito Brothers member Rick Roberts, ex-Beach Boys singer/guitarist Blondie Chaplin, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel of The Band, with ex-Byrds Michael Clarke and John York. Clark initially called his band "The 20th Anniversary Tribute to The Byrds" and began performing on the lucrative nostalgia circuit in early 1985. A number of concert promoters began to shorten the band's name to "The Byrds" in advertisements and promotional material. As the band continued to tour throughout 1985, their agent decided to shorten their name to "The Byrds" permanently, to the displeasure of McGuinn, Crosby and Hillman. Clark eventually discontinued performing with his own "Byrds" band, but drummer Michael Clarke then continued on with Skip Battin (occasionally using ex-Byrds York and Gene Parsons, also), forming another "Byrds" group, prompting McGuinn, Hillman, and Crosby into going on the road as "The Byrds" to attempt to establish claim to the rights to the band name. Their effort failed at the time, and Gene Clark, primarily due to his involvement with the act that didn't include them, was not included in their reunion. David Crosby finally secured rights to the band name in 2002.

In 1987 So Rebellious a Lover became a modest commercial success, but Clark began to develop serious health problems; he had ulcers, aggravated by years of heavy drinking (often used to alleviate his chronic travel anxiety). In 1988, he underwent surgery, during which much of his stomach and intestines had to be removed.[citation needed]

A period of abstinence and recovery followed until Tom Petty's cover of "I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better" on his 1989 album Full Moon Fever yielded a huge amount of royalty money to Clark who quickly reverted to drug and alcohol abuse. The Byrds set aside their differences long enough to appear together at their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in January 1991, where the original lineup performed several songs together, including Clark's "I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better".

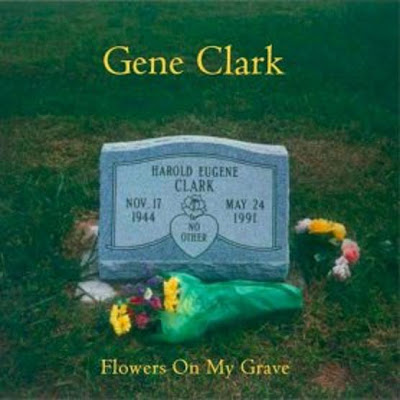

However, Clark's health continued to decline as his drinking accelerated. He died of natural causes on May 24, 1991 at age 46. The coroner declared he succumbed as a result of "natural causes" brought on by a bleeding ulcer. He was buried at Saint Andrews Cemetery in Tipton under a simple headstone inscribed "Harold Eugene Clark - No Other."

Discography

Studio albums

* Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers (1967)

* The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark (1968) – with Doug Dillard

* Through the Morning, Through the Night (1969) – with Doug Dillard

* White Light aka Gene Clark (1971)

* Roadmaster (1973)

* No Other (1974)

* Two Sides to Every Story (1977)

* McGuinn, Clark & Hillman (1979) – with Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman

* City (1980) – with Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman

* Firebyrd (1984)

* So Rebellious a Lover (1987) – with Carla Olson

Live albums

* Silhouetted in Light (1992) – with Carla Olson

* In Concert (2007) – with Carla Olson

* Silverado '75: Live & Unreleased (2008)

Compilations

* Echoes (1991) – Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers with additional early material

* American Dreamer 1964–1974 (1993) – best of

* Flying High (1998) – anthology

* Gypsy Angel (2001) – collection of demos recorded between 1983-1990

* Under the Silvery Moon (2001) – collection of previously unreleased mid-80s material

* Set You Free: Gene Clark in The Byrds 1964–1973 (2004) – collection of material recorded with The Byrds

* Here Tonight: The White Light Demos (2013) – collection of demos

Covers and tribute songs[edit source

During his career and subsequent to his death, Gene Clark's songs have been covered by a number of artists. Ian Matthews was an early promoter of Clark's songs, covering "Polly" on Matthews' 1972 Journeys from Gospel Oak album, and "Tried So Hard" on his 1974 Some Days You Eat The Bear album. Death In Vegas and Paul Weller covered his song "So You Say You Lost Your Baby" on their 2003 album Scorpio Rising. In 1993 the Scottish band Teenage Fanclub recorded a tribute to Clark on their album Thirteen entitled "Gene Clark". In 2007, two of his songs were recorded by Alison Krauss and Robert Plant on the T-Bone Burnett produced Raising Sand: "Polly Come Home" and "Through the Morning, Through the Night." Also in 2007, Chris and Rich Robinson released a live version of "Polly" on their Brothers of a Feather: Live at the Roxy album. This Mortal Coil covered "Strength of Strings" from his LP No Other and "With Tomorrow" from LP White Light. Soulsavers with Mark Lanegan recorded a version of "Some Misunderstanding" from No Other on their 2009 release Broken. Title Tracks recorded a version of "She Don't Care About Time" on its 2010 release, It Was Easy. The song has also been covered by Sex Clark Five and Flamin' Groovies.[citation needed] The song "Gorgeous" from Kanye West's 2010 album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is based on elements of the Clark/McGuinn song "You Showed Me".

________________________________________________

Old hippies never die, they just ramble on.

-lk |

| 3 L A T E S T R E P L I E S (Newest First) |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 12/08/2013 : 15:33:20

Below are some very engrossing, enlightening and enjoyable reads...about Gene, our favorite Firebyrd; his music, his life.

NO OTHER-full album play!..listen and read on.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPghGSOrHFk

"NO OTHER"--Gene Clark

....................

The Byrds, hailed in the beginning as the American Beatles, turned out to be as fractious and egotistical as their UK counterparts were tight, gang-like and grounded. Possibly for this reason, the Byrd deemed to be the heart, the driving force of their rich music, has shifted over the years: initially it was Roger McGuinn, architect of their jet-age jangle, and it stayed this way during the group's lifetime; the spotlight shifted to the smug hippydom of David Crosby in the Seventies afterburn; and then on to Gram Parsons, somehow deemed the most 'authentic' Byrd in the country rock-obsessed Eighties.

Sweet Gene Clark. How sad and typical of his ill luck that he died in 1991, just as the consensus swung his way.

He had been the most handsome Byrd and their finest and most prolific songwriter, but on stage he was sidelined as tambourine player, a proto-Davy Jones. Fear of flying meant he would leave and rejoin the group on several occasions - it also hindered the promotion of any subsequent Clark projects. For decades, ludicrously, he remained a well-kept muso/fanboy secret.

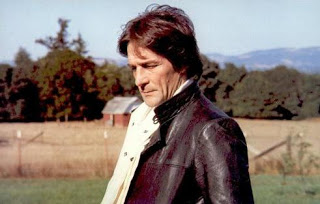

No Other, a dark, baroque album is central to Gene Clark's critical rebirth. The artwork is a giveaway, a collage of Twenties glories with Anita Loos and other sexy flapper chums at its heart. Hollywood Babylon revisited. On the back, rugged Gene appears in mascara and billowing drag. He looks quite terrifying. Drawing parallels between the decadence of the Twenties and the coke-addled extravagance of the mid-Seventies, Clark fashioned a suite of songs that was a pure, personalised Americana, a distillation of all he had seen and learnt from his childhood in Missouri and his adult years in LA. Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks had talked of their aborted Smile album being "a Gothic American trip"; likewise, Clark's fellow country rock traveller Gram Parsons once expressed a dream of creating Cosmic American Music. No Other was the real thing.

Aside from his mastery of melancholy, there had been few clues in Gene Clark's back pages that he would deliver something this wild and dark - his last fully realised album had been the beautiful but spartan White Light in 1971. The turning point was meeting the producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye, a Steely Dan acolyte and one-time colleague of the wunderkind producer Curt Boettcher. Their shared love of Zen Buddhism, booze and drugs took them to the Village Recorder studios in west LA in March 1974 with $100,000 from Asylum Records burning a hole in Kaye's pocket.

He had just massively overspent on a Bobby Neuwirth album and now saw No Other as "my Brian Wilson extravaganza". As for Clark, the record was "all about soul searching". Eight songs in six months suggest that there was plenty of that.

Life's Greatest Fool is a misleading opener, being an exercise in fine country rock with only the gospel harmonies and cautionary philosophy there to cause a stir. The gothic undertow of Silver Raven, all "darkened waters" and "troubled sky", veers into Johnny Cash territory. The title track is where things take a wholly different turn, a hypnotic almost funky piece which occupies the same niggling darkness as David Bowie's Golden Years. Apparently it took a week before the musicians got their first take and you can sense the numbness, the intoxication.

Strength of Strings is the album's centrepiece. The brief Clark set himself was to convey the subconscious way in which music is created, how it can be so magical, spiritual, overwhelming. No less. He pulls it off with a slow-burning intro of near-oriental harmonies, almost treading on Crosby, Stills and Nash's toes, while Kaye adds layers of ghostly church voices until the whole thing explodes with Clark's tearful tones - "In my life the piano sings, brings me words that are not the strength of strings." Side 2's opener, From a Silver Phial, is almost light relief, though its lyric - criss-crossing between the tale of a cocaine casualty and a sensual master-servant saga from the old South (or is it Hollywood?) - is as much the opaque heart of No Other's mystique as Strength Of Strings' grandeur.

The eight-minute Some Misunderstanding came to Clark in a dream which he dictated to his wife in the middle of the night. Its vagueness is its beauty, beginning as a meditation on how to take a relationship forward then ruminating on the recent death of Gram Parsons - "We all need a fix, but at times like this, doesn't it feel good to stay alive?" It soars and floats over pedal-steel and organ interplay (the cream of LA session players, anyone you care to name) and hangs eerily in the air, unresolved. Passing through The True One, another country-rock interlude, we reach the climactic Lady of the North, "like silver on the ocean shore". Clark sounds awed, lovestruck, and never sang better, reaching from rumbling baritone to near-falsetto (think of the middle eight of Elvis's Any Day Now and you're close). Dense and hypnotic, his voice weaves in and out of the piano, cello and electric violin - when the shimmering coda arrives it is pure release.

Over the years No Other has been lauded by some but frequently criticised for over-ambition (David Geffen at Asylum concurred and put no promo effort in - it consequently sold zip). This is conservatism on a par with Mike Love's criticism of Pet Sounds. Recorded in a stultifying era of newly-minted and consequently too-cosy singer-songwriters, the result of Gene Clark's search for America's dark heart seems all the more impressive. And it sounds deeper and stronger with each passing year. What a terrible pity he isn't around to receive his standing ovation.

Posted by Bob Stanley at Monday, January 16, 2012 - croydon municipal

............................

GENE CLARK - ZENMASTER

By Steve Burgess 1976

"...In the end they traded their tired wings

For the resignation that living brings

And exchanged love's bright and fragile glow

For the glitter and the rouge

And in a moment they were swept

Before the deluge ..."

Jackson Browne: "Before The Deluge"

That song is an elegy, a dirge, a lament. For Jackson Browne,

boy-child of spiralling sixties circumstances - Ciro's where The Byrds

parcelled light up into musical segments, and Sunset Strip where the

strange young girls offered their youth on the altar of acid - it is a

statement on a generation. From an outsider. And, consequently maybe,

earnest family-man Jackson has presented us with a capsule of truth. No matter which flank you choose to attack the song on, superficially naive though it is, he has the angle covered. For so many resigned their colours, returned to tug at society's skirts that the deluge, the personal apo-calypse of a generation (whatever a generation is) is now seen by Dylan's Mr. Jones as a passing cloud, an aberration, another youthful media-hyped gangbang. Not so, but why bother to prove it now. The Byrds took it to the limit. And The Eagles are goin' back.

Rock is a communications system fallen into disuse, like smoke

signals. When Love and The Byrds hit the Strip, electric rock was still as brand-showroom-new as the dishwasher of the future - maybe rock will be the dishwasher of the future - and, as baffling new musical and linguistic vocabularies hit the West Coast like some pack of outlaw hikers, a revolution hit the music industry, if nowhere else. California dreamin' became a new parlour game: cigar chomping hack tunesmiths no longer poured their soft-headed conception of teenage life and love over the radio landscape and suddenly it seemed everyone from wholemeal highschool kids cutting out on Mary Jane-wanna to crawling kingsnake nightpersons had a band whose music soundtracked their personal reality.

Then gone in the spin of a wheel; somehow image got a foot in the door, maybe never left L.A., where all the world is but a billion dollar sensurround movie set ... never quite made it to San Francisco, Tubes notwithstanding ... glitter and rouge spread like margarine, Faye and Peter, Britt and Rod, Vincent Price and Alice Cooper and everybody all moneybound on the Las Vegas Flyer. Goodbye to the kid next door with the red Stratocaster and let's have a warm welcome for dry ice, perspex drums and leather-look machismo. Frank Zappa once held forth: "A freak cares what he looks like, a hippie doesn't". Guess there were a lot of freaks about.

The humble, bumbling hippie has a financial empire built on his shoulders, and, with Vietnam out of the way, teenage America could lapse back into the trivial, although it kept the stash and the stereo and demanded, "Feed me". Mr. Jones still didn't know what hit him but, with hindsight, it seemed harmless enough.

In music, a few people didn't know when to shut up and behave, which of course, might help their record companies to shift a few more units. And, probably, their audience is confined forever to the few survivors of the deluge, to use "Jackson's Metaphor", unless, somehow, like the Starship, they can cross upmarket. Like playing Russian Roulette with five loaded chambers.

Gene Clark left The Byrds after "Eight Miles High" and shut up, only to find himself a unique style of self-expression.

But to hell with sociological background (pause) , ladies and gentlemen (fanfare), Gene Clark, Zenmaster. (Applause).

Harold Eugene Clark, born Tipton, Missouri, 1941, a simple country boy of a large country family, no doubt spent a lot of nights listening to whippoorwills and winds; mournful mountain music is his stock in trade. He professes to making surf music in school, graduating to a twelve-string folk thing on the same circuit as journeymen Brewer and Shipley, before being appropriated by the New Crusty Nostrils to play on two albums and that monument of disgusting ephemera, "Green Green". No doubt fully revolted, Gene cut out in L.A. and hung around the Troubadour where Beatlemaniac McGuinn regularly performed select-ions from the furry four's song-book. Gene began to sing along, the story goes, as did another ex pre-packed folkie casualty, chubby David Crosby. After a few amply documented false starts and many cigarette butts, The Byrds appeared, stomping cuban heels and blast-ing ozone all over the airwaves.

Gene was genuinely the moody one, gaunt, rattling tambourine, supplying their best homegrown material, yearning even then. Witness "Here Without You". Like Rothmans, The Byrds became international, had to go places, but Gene balked, he'd seem an aircrash first-hand; no way did he want to fly, "...the pressure did me in." He rejoined a couple of times but couldn't cut it, and decided that solo was the way to be, a personal singer wanting to make a personal statement. For The Byrds, "5D" came and went while Gene meticulously constructed the world's first country-rock-super session album, "Gene Clark And The Gosdin Brothers", with Chris Hillman, Mike Clarke, Leon Russell, Glen Campbell and Clarence White. It was finally released in early '67, the same week as "Younger Than Yesterday". There were few completists, scholars and connoisseurs around then: Gene was simply forgotten and the new Byrds album had the same effect on Gene as Kryptonite used to have on Superman. No contest.

Gene stepped up the gigging, ran into Doug Dillard and between them they collected an amorphous gaggle of musicians to form the Expedition, a band woefully out of step with public taste, a true contemporary country band in a world that wasn't exactly overjoyed by The Byrds' perverse-seeming, Parsons-inspired leap into country with "Sweetheart of the Rodeo", a move in which Doug had a small picking hand. It seemed both Gene and Doug had room to stretch out in their framework and the first album seemed to bear this out. (A&M SP4158 1968). For this, Gene collaborated heavily with Bernie Leadon, only "Out On The Side" was written alone, and that stuck out like a frozen nose. Nevertheless, it's an incredible waxing, lively and confident; it's companion piece, "Through The Morning Through The Night" (A&M SP 4203) which emerged in 1969, wasn't so strong, a diverse conglomeration pushing two ways. Gene was being forced into a stylistic corner by ripsnorting bluegrass with which he was uncomfortable, although "Polly" is a breathtaking wispy song in a style he would later explore, chart and claim, and his readings of the Everly's "So Sad" and Lennon-Macca's "Don't let me down" fill the room with the Clark primal melancholy. Gene then split; and the Expedition went on to become wholly unnecessary as Country Gazette and Pseudo Burritos.

By now Gene had already thrown away the key on two albums worth of material recorded before the Expedition, and he now embarked on another round of aborted projects: A single with the original Byrds - "One In A Hundred" which surfaced on "Roadmaster" (after the "White Light" cut) - and a session for the third Burrito's elpee which produced "Here Tonight" - variously on "Roadmaster", "Close Up The Honky Tonks" and "Honky Tonk Heaven - which would have eclipsed everything else on it; maybe that's how it got shelved. More backlogs, brick walls; Gene moved to Mendocino, where something happened to Gene; no doubt it was always there, but communing in

solitude with his twelve-string in '70 and '71 exposed a tradition to which Gene Clark belongs, musically unparalleled but with clear literary and spiritual precedents. It is apparent. It is there on "White Light", a verbal facility once devoted to love songs, turned in on itself, twisted into alien blueprints of personal philosophy.

"White Light", produced by Jesse Ed Davis, released 1971 on A&M SP 4292, is a blazing, multi- faceted statement. Always the unstated enemy of the rational, the orthodox, Gene now attacked perception itself; by the time "No Other" was made, Gene finally had no need of even that, but by this time those who had listened to "White Light" could make that transition. However, the white-walled room "out on the end of time" became no longer a metaphor but an actuality as Gene emphasised one-ness with the

universe, the white light once talked of by acid-heads, the living nirvana in which all references cease to operate. In fact the way of Zen...

The album opens with "The Virgin", with his new-found, almost Shakespearian, use of language directed towards connecting "The Virgin" - a virgin only in the abstract - with "wisdom's karmic ocean"; the revelation that "lifeforms are insane" becomes "the melodies of meaning/ the sad song she learned to sing". Like an Old Testament prophet, he pushes his created character through a re-birth with which she must come to terms, and asks, "was this her revolution, just a child in love's crusade?"; she is pushed past a point of disillusionment, on the far side of which lies only insanity or acceptance. Gene clearly sympathises, and, himself, accepts.

In "From a Spanish Guitar", Gene, unique for a rock musician, presents himself as no more than a mouthpiece for the elements, for

children and the insane, all of which "flow safe through my soul and my brain and a Spanish guitar". By giving voice to these things, but allowing them to express no opinions, they make no point but to assert their existence ... as in Zen, they must be understood on their own terms. Later Gene returned to his obvious belief that music is, in itself, sometimes one of the purest everyday forms of the Zen philosophy, (since the conversion of sound into meaning is such a subjective process), in "Strength Of Strings" only in a purer form, since, there, all that protests its existence through Gene is the music itself.

"White Light" itself is a difficult riddle; seemingly too personal to

penetrate, it paints pictures of a village and its people "enlightened by the land", but also seems to encapsulate Gene philosophy. Anyone familiar with Zen will be familiar with the precept: "Those who know do not speak, those who speak do not know". I, as the writer of this would find this insoluble if it wasn't for the facts that, through Zen, I need not examine it ... nevertheless; in "White Light" that maxim is interpreted: "The communion of the forces take delight with the theory that no tongues can read or write ... white light." Indeed.

But, like all creations, Gene's songs need an audience; one acclimatised [sic] to the oblique and the metaphorical ... once there was a spateof extravagant claims that rock lyrics were capable of standing as poetry,mostly confined to the hysterical drivellings of indulgent jazz critics. Not so, poetry is dehydrated, disciplined ideas, economy is necessary; rock lyrics have a tendency to dissipate, to fall apart in the mind - if they haven't done so in transit from speaker to ear. In between these poles are the media of print, sources, texts. We have to cast an eye over what are ref erred to as "cult" books, things that, in conventional terms, hit the

impressionable reader right between the frontal lobes and which he is

conventionally supposed to grow out of: like bluegrass, rock, dope, and sassafras tea. Mixed blessings come of them, secretaries gobbling Von Daniken, active lives reduced to infinite indecision by overdoses of I Ching, Manson taking "Stranger In A Strange Land" as a blueprint and an excuse ... but also the permanent redirection of aimless lives through "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test", "On The Road", or Guthrie's "Bound For

Glory", and the rediscovery of a sense of wonder and sensory excitement through Brautigan, Tom Robbins or even the catch-all "Zen And The Art Of Motor-Cycle Maintenance". That word again. Read through a cross-section, and, ultimately, depending on where your ethics come from, you will find strong traces of what could be called "Nihilism" - lack of responsibility - but which I prefer to term Zen - a sense of continuity; of what is relevantand what is ephemeral, dead wood.

On the psychotropically-steeped West Coast of America, cults regenerate infinitely, and the biggest, brightest, five-star legend is that of Don Juan, brujo (medicine man, wizard, sorcerer, shaman, choose one), the great brown hope of the acid generation as it sits around debilitated, thirsting for new texts. Don Juan, new readers start here, is the hero of a series of four books by Carlos Castaneda, who supposedly met the old Hopi Indian at an Arizona bus depot while researching for his PhD and became his pupil, embarking on a decade-long struggle to become a brujo himself, through learning to "See". Castaneda has now admitted Don Juan to be a figment of his fertile imagination, confirming the suspicions of many who found Castaneda's stupidity and credulousness (in the books) to be literally, too much to be true. Nevertheless, the teachings of this

fictional ultimate guru represent an extraordinarily clever and successful attempt to recycle whole fertile areas of Western and Eastern thought into one hybrid discipline and philosophical system. Castaneda, with one sustained metaphor, kept millions dreaming in the wake of the soured Alternative American Dream, stopping off along the way at Nietzsche, Sufi Tales, Tim Leary, the Bhagavad-gita, the I Ching, Crowley and the Tarot, Vonnegut, and, particularly, Zen. A priceless con; and one that loses nothing from the fact, because that metaphor has created a new vocabulary for others to communicate with. The ends justify the means; Don Juan enables Castaneda to fly and refuses point blank to categorise whether this is fact or an illusion; as far as he is concerned it is ir-relevant, the distinction means doodly-squat. This is Zen thinking. It's also a good commentary on the value of the books. The Eagles wrote "Journey Of The Sorcerer" and "Visions" about Don Juan and announce them from stages everywhere as "for all you Castaneda freaks". Garcia sings "I was blind all the time, I was learning to see" ("Help On The Way") with an inflection that leaves no doubt about its meaning. And Gene Clark wrote "Silver Raven" - a creature with origins in Don Juanology - and sang it on tour with Roger McGuinn, a year before it came to rest on "No Other", the album which gives Castaneda's Folly a practical expression. Castaneda gave Gene Clark, Zeamaster, a framework to work in.

Nevertheless, "White Light" sold like umbrellas in the Sahara, in spite of favourable critical action, although these plaudits were more directed to the honest grainy sound than actual content, and '72 saw Gene clearing the air for his no doubt rather nebulous new direction. He assembled a stalwart band of faithfuls - Clarence White, Sneeky Pete, Spooner Oldham, Mike Clarke and Byron Berline - and in April to June cut eight tracks for a projected album which eventually metamorphosed into the Dutch semi-compilation "Roadmaster" (A&M 87 584 IT). The reasons behind Gene dropping the whole project like a hot burrito are uncertain, certainly the character of the songs, with the exception of the ugly, out-of-character "Roadmaster" and the oblique, post-apocalyptic "Shooting Star" (obviously a "White Light" holdover), suggest a man working through an old catalogue of songs which he had by then, outgrown.

This obsession with setting business in order led Gene and Jim Dickson to enter Columbia's L.A. studios that year to re-mix and re-record vocals for Columbia's projected re-release of the Clark/Gosdins album. In the space of a week they transformed the thing into "Early L.A. Sessions" (Columbia KC31123), a lovingly documented artefact, but minus "Elevator Operator" which supposedly did not stand the test of time and brought the playing time down to a ludicrous 23 minutes. Essential seminal stuff nevertheless, particularly "Tried So Hard", "Keep On Pushing" - to which the label enigmatically appends "Doug Dillard on electric banjo" for some obscure reason - "So You Lost Your Baby" and the eerie "Echoes": This was Gene's first foray into the human psyche, and one which once frightened your commentator truly rigid for a deeply personal reason, because "Echoes" reflects the fact that lovers reach points from which they can no longer continue together, but for no nameable reason, and with no loss to the forces that held them together, as I was finding out, regretfully, at the time I first heard the song. '72-'73 also saw the renowned re-formed Byrds debacle on Asylum SYLA 8754, the label to which Gene had recently signed. To some it seemed that the album was to be used as a vehicle to shoot Gene to stardom status, but he wasn't having any, content to dredge up "Full Circle Song" (also on "Roadmaster" and probably dating, therefore, from as early as '68) and "Changing Heart" which neither adds nor subtracts anything from Gene's philosophies, unlike "Full Circle" which is his expression of the Eastern notion of a cyclical universe, as portrayed in the I Ching and Tao Tse Ching. Gene also paid tribute to Neil Young by recording "Cowgirl In The Sand" and "See The Sky About To Rain". both sensitive, if detached, readings; the best that can be said for the album is that Gene fared better in the ego-centric paws of producer Crosby than did McGuinn and Hillman.

However, deByrded McGuinn was now truly out on the side along with Gene, who left his North California eyrie to share a house with him in '73, and, during this time, to sit in on the "Adventures Of Roger McGuinn" tour, where he per-formed "Silver Raven" to a few select, but disinterested

audiences. And with that, Gene Clark left the musical community to its own devices.

The facts pertaining to the release of a record album by Gene Clark on Asylum SYL 9020 late in the year 1974 are plain and clear enough; fifteen musicians, eight back-up singers and producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye helped him make it in L.A. and San Francisco over a period of six months. The cardboard, paper and plastic object they spawned is conversely, something that over-reaches itself and becomes impossible to rationalise or focus on. The cover is deliberately and monstrously inappropriate; every image, the whole conception, is totally dislocated from the content of the music. And so it becomes irrelevant, and, mocking the whole concept of record sleeves as it goes, winks out of existence slowly, leaving the listener no clues to help deal with what it contains.

The lyrics are printed on the inner sleeve, and that's another red herring. These lyrics should not, and cannot, stand that sort of scrutiny since most don't make any conventional sort of sense; they are inseparable from the music and must not be approached, it would be like trying to read the maker's name on a rainbow. And Zen teaches that words are a clumsy vehicle for communication, since they can only present ideas as tiny particles of information, and not as totalities. So ignore it, and there's only the music left.

Like "Astral Weeks", "No Other" comprises only one multi faceted song. Play it, and the twin speakers become twin facing mirrors, endlessly regenerating, a link with infinity; its subjects are reality and time and spirituality and dreams and how to come to terms with the world. And for this it is a totally unique work; rock has always had its intellectuals with palpitatingly eager audiences ready and willing to snarf up their ephemeral pap as significant. Maybe I do Gene Clark a disservice to treat his music this way, as heavy duty profundity. At least I am convinced this record should be taken seriously. It's not merely entertainment.

Side one opens with "Life's Greatest Fool", a mid-tempo rocker building slowly to piledriver level, Gene declaiming a long series of dislocated images and observations, some obvious, some mysterious cats-cradles, asking, "Could these be reasons why man is life's greatest fool?" The term "fool" is ambiguous anyway, since it could be taken to mean "innocent" as in the Tarot, and, paraphrased, the song asks whether man is misguided to continually question and attempt to explain what he perceives. The alternative is the Zen outlook ... and Don Juan tells Castaneda that he must cut down on the internal dialogue if he is to "See". Gene Clark re-affirms this, and gives a model for this point in the image of the "Silver Raven", the next track, and a creature from out of Castaneda's back pages. In this song, the raven contemplates a coming, nebulous, apocalypse. Four times Gene asks whether he has seen (Seen?) these things, seen "the old world dying". "Silver Raven" celebrates the insularity of man's view that he is in control of his world, and advises spiritual unity with the elements.

"No Other" follows. and sets these conclusions out again almost in the form of an I Ching hexagram: "Then the pilot of the mind must find the right direction". Distilled, the song says that to personify love as "God" and to commune with him alone, is to Deny "the tide of life that flows in each direction". Gene sees God as a form of human collective consciousness; "All alone we must be part of one another", and the side closes with "Strength of Strings" in which Gene claims that music works through him rather than vice-versa. "Strength Of Strings" is a vast, elegaic, panoramic hymn and everyone performs as if posessed. It is its own explanation, a self contained world, in which "I am always high, I am always low, There is always change" - the Eastern notion of a cyclical universe again, first explored in "Full Circle Song".

"From A Silver Phial" leads off the second side and is essentially a love song, the first of two. "Phial" is a highly explicit song about a

particular woman and communicates nothing at all, except for a lingering impression strong enough to make you feel that you know her from somewhere. The virgin? Visionary use of words "... said she saw the sword of sorrow sunken in the sand of searching souls" more use of the universal symbolism of the Tarot. A Zen love song. Like love, it is beyond rational thought, and contrasts well with "Some Misunderstanding" which follows, in which Gene talks directly to the listener about fate and the future. He seems to be exposing his fallibility as a philosopher, examining his position in detail and expressing his human fears, but returns to a basic philosophy - "We all need a fix at a time like this but doesn't it feel good to stay alive". "Fix" is used for its ambiguity, its overtones of smack, but

primarily in the sense of a bearing, a direction. The rest of the album acts out the directions ... The penultimate song, "The True One" is lighter in sound and context than the rest, a throw-back to simpler times in its construction, a recollection lyrically of Gene's rock star past, which he plainly regards as mis-spent - presumably because of its emphasis on the material - and presented as a long stream of mottoes and aphor-isms, like a Sufi tale. It also contains an observation of reality; he plainly believes himself to have evolved into a different reality, separate and distinct, the true one.

And finally, in "Lady Of The North", the second love song, he sings of his alternative reality as a change in the wind that must come, natural and destined. The song has an immense rhapsodic grandeur, an illusion of free flight. "Ah, fine lady of the North, like silver on the ocean shore "No Other" is now deleted. Gene Clark has no recordings currently available in this country. The album he has been working on for the past year, reputedly a "Country-Motown" synthesis, does not appear. Asylum have no release scheduled.

Gene Clark was "pretty happy" with "No Other". "You could call this a transition for me. I'm moving into another, bigger arena."

Good grief, some of us think "No Other" is one of the finest albums ever cut. Where can he take us to next? Trust the man who knows the Strength of Strings.

STEVE BURGESS

DARK STAR #3

DARK STAR PUBLISHING 1976

NO OTHER

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GilrLIwBJE8

________________________________________________

Old hippies never die, they just ramble on.

-lk |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 12/08/2013 : 15:25:12

Gene Clark: Here Tonight: The White Light Demos

By Matthew Fiander 31 May 2013

PopMatters Associate Music Editor

For A Spanish Guitar

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TA4kkb5Hew

In 1970, Gene Clark left Los Angeles. This was four years after he left the Byrds, two years after beginning the Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark with Doug Dillard, and one year before he would record and release his solo record, White Light. Clark left LA disillusioned, but not in the post-Altamont way you’d expect in 1970. Clark claimed to be tired of the “star-making machine” but he was probably just tired of the way it had misshapenly made his star. His years with the Byrds were fruitful ones, and they garnered him attention, though that attention was problematic in several ways. For one, it made for some serious clashing with his bandmates, but it was an attention always in the shadow of Bob Dylan: the band’s first hit was “Mr. Tambourine Man”. The band, especially in the early days, recorded plenty of Dylan songs, and the link was one they couldn’t shake, or maybe didn’t want to. Clark’s own songs, through careful study or osmosis or both, resembled Dylan’s. They were never quite as verbose or strange, but they did seem geared toward some weird America simmering under the surface. Under, perhaps, those LA streets he grew so embittered by.

So if the purity of his artistic integrity was part of what drove him out of LA to the open spaces of California near Mendocino, there was probably also a bit of ego there. His disillusionment wasn’t the collective kind we talk about when we talk about 1970; it was personal and true, but also complicated. However, it did lead us to another complicated moment, Gene Clark’s first true solo record (excluding here his 1967 record with the Gosdin Brothers). White Light is an album now oft-lauded but then commercially ignored. It was the culmination of Clark’s musical moves since the Byrds. His work with Doug Dillard helped distinguish himself from Dylan’s influence, and those songs sounded more like they existed on a new ground, a ground Clark knew well.

White Light, though, was Clark fully at home, literally and figuratively. In writing these songs in the new wide-open spaces he lived in, with new wife Carlie McCumming, Clark was finally fully and wholly himself. The album is a personal, stripped-down one, one that has intricate layers but never feels overstuffed. Twanging guitars and harmonica, and the dust of acoustic strumming, and Clark’s pristine voice swirl around each other, but they also all get wide birth, taking time to spread out, much in the way the land around Clark might have. Sure, there’s still a hint of Dylan there—in the strange details of “The Virgins” and, of course, his version of “Tears of Rage”—but these moments felt more like Clark twisting Dylan’s inscrutable genius into something more personal, more approachable, more, well, him.

Now Omnivore Recordings have given us the demos to the album on the new collection Here Tonight: The White Light Demos. It’s a set that does exactly what you expect a demo collection to do, and yet gives you an impact you might not expect. These are just Clark and his guitar and harmonica, and you get to hear the energy of early takes of “White Light” and “The Virgin” and even a brief, fledgling take on “With Tomorrow”. Clark’s voice is as beautiful here as it is on the record, and there’s not a scuff or scratch to be heard on these recordings. They could be, in fact, their own proper album. The demos also don’t deviate all that much from the studio version of White Light, at least they don’t seem to at first. It’s tough to get much leaner than the album versions of these songs, so these demos don’t seem all that spare in comparison.

However, if both collections are intimate, they get at different intimacies. The studio version is an approximation of intimacy, an image of the feeling that began the songs. It’s a brilliant image, not one to be undersold, but Here Tonight does something different. Unlike so many home recordings, which sound like claustrophobic communiqué between the player and their recorder of choice, these songs actually convey the relationship between Clark and the new space around him. You can hear it around the echoing harmonica on “White Light” or in the stretched keening of his voice on “Opening Day” (originally a bonus track on the 2002 reissue of White Light). These are a document of an artist in his element, and the results are as beautiful as we expect them to be, but striking in their poignancy, in how they make the familiar ring new, and perhaps more true, than the version we know already.

The previously unissued tracks here add to our understanding of Clark at the time, though they succeed to varying degrees. “For No One” is the best of the bunch: a quiet, bittersweet tune that smooths out Clark’s usually sharp harmonica playing and lets Clark play with a gentle and affecting falsetto. It’s a song that takes full advantage of the space Clark is working with, but other unreleased tracks “Please Mr. Freud” and the brief “Jimmy Christ” feel a bit out of his wheelhouse, a few last attempts to shake off ill-fitting, Dylan-esque eccentricities. “Here Tonight”, once recorded by the Flying Burrito Brothers, is a much better reveal for Gene Clark as an artist, luxuriating in his songs, stretching his legs as he admits “I don’t want to be anywhere but right here tonight.”

Gene Clark found himself with this record, though not enough people found him. The record didn’t sell well, and his joy and comfort wouldn’t last. He would later return to LA, and tour, and his marriage would crumble; he got tied up in alcohol and drugs and died in 1991. But White Light was and is a crystallizing moment for him, for the songwriter’s songwriter. It’s an album that earned its acclaim over time. Here Tonight: The White Light Demos doesn’t help us re-see that album, but rather it reimagines the player himself, a man who—for a short time in his tumultuous artistic life—finally struck that balance between comfort and creativity. This is the bittersweet sound of someone who found, however briefly, home.

Where my Love Lies Asleep

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60fFDCg1fGQ

Here Tonight

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zzz1DvvMRoY

For No One

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0oOna4l_ug

________________________________________________

Old hippies never die, they just ramble on.

-lk |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 12/08/2013 : 15:19:59

The Fantastic Expedition Of Dillard & Clark

Train Leaves Here This Morning

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSrDtl-3eJs&feature=related

The Radio Song & DOn't Come Rollin'...worth a second listen!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fi341PWDfC0

Dillard & Clark was a country rock duo which featured ex-Byrds member Gene Clark and bluegrass banjo player Doug Dillard. The group was formed in 1968, shortly after Clark departed The Byrds, and Dillard left The Dillards. They were backed up by, among others, Bernie Leadon, Chris Hillman, Sneaky Pete Kleinow, Byron Berline, Michael Clarke, and Laramy Smith.

THE ALBUM...

The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark is a country rock album by Dillard & Clark. The album was recorded in 1968, shortly after Clark departed The Byrds for the second time, and Dillard left The Dillards. The album is hailed by critics and musicians as a masterpiece of the country rock genre.

1. "Out on the Side" (Clark) – 3:49

2. "She Darked the Sun" (Clark, Leadon) – 3:10

3. "Don't Come Rollin'" (Clark, Dillard, Leadon) – 3:49

4. "Train Leaves Here This Morning" (Clark, Leadon) – 3:49

5. "With Care from Someone" (Clark, Dillard, Leadon) – 3:49

6. "The Radio Song" (Clark, Leadon) – 3:01

7. "Git It On Brother" (Lester Flatt) – 2:51

8. "In the Plan" (Clark, Dillard, Leadon) – 2:08

9. "Something's Wrong" (Clark, Dillard) – 2:57

The following bonus tracks have been included on CD reissues of the album:

* "Why Not Your Baby" (Clark) – 3:41

* "Lyin' Down the Middle" (Smith, Clark) – 2:17

* "Don't Be Cruel" (Elvis Presley, Otis Blackwell) – 1:53

Personnel

* Gene Clark - guitar, harmonica, vocals

* Doug Dillard - banjo, fiddle, guitar

* Bernie Leadon - banjo, bass, guitar, vocals

* Chris Hillman - mandolin

* Sneaky Pete Kleinow - pedal steel guitar

* Jon Corneal - drums

* Michael Clarke - drums

* David Jackson - bass, piano, cello, vocals

* Byron Berline - fiddle

* Donna Washburn - guitar, tambourine, vocals

* Donald Beck - mandolin, fretted dobro

* Andy Belling - harpsichord

Production

* Producer: Larry Marks

* Recording Engineer: Dick Bogert

* Art Direction: Tom Wilkes

* Photography: Guy Webster

* Liner notes: Bob Garcia

________________________________________________

Old hippies never die, they just ramble on.

-lk |

|

|