| T O P I C R E V I E W |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 20/09/2012 : 13:42:49

(thx, Rick...really interesting as he answers all our 60's Byrd's questions)

Interview with Roger McGuinn of the Byrds

February 14, 1970, Indianapolis Coliseum and May 3, 1969, DePauw University

By Vincent Flanders

(Copyright © 1995-2010 Vincent Flanders)

One of the best interviews Roger ever gave he gave to me back in 1970. This interview was before the days of spin doctors and 14-page forms interviewers had to sign about which questions they can and can't ask.

I've decided to combine a not-quite-as-good interview from May 1969 with the 1970 interview. I've also rearranged some sections to try to make the interview more chronological.

There's an interesting story behind this photo of Roger taken at DePauw University. The main Byrds site was originally at the University of Arkansas and they had a link to this interview, but took it down. Here's the email from September 6, 1995, explaining why:

Sorry man. I made the link, but I got a letter from Roger asking that I remove it due to some statements he made that he now considers inappropriate I guess. He didn't like himself looking fat in the picture either. We all have our little vanities. I thought it was a good interview myself.

Of course, the irony is the photo of Roger was taken when he was actually fairly thin. The shirt was just puffed out a bit. As Al Pacino said in the movie Devil's Advocate, "Vanity, definitely my favorite sin."

Flanders: Why, in the beginning, didn't you get a good drummer? Why was it Mike Clarke instead of someone like (current drummer) Gene Parsons?

McGuinn: We were not very systematic about the formation of the group. It happened very naturally. Gene (Clark) and I just sort of blended together one night (McGuinn was singing Beatle songs at the Troubadour, an LA club) and decided to form a duet. And the very same night, within ten minutes after we had gotten our thing together with some songs that we both collaborated on like (we'd) written a couple of songs in two minutes, right? David Crosby comes along and says, 'Can I sing harmony?' and we said 'Sure' cause I'd known David from 1960 when I was out on the coast working with the Limelighters. And so there was David singing and we had a trio.

David took us over to Jim Dickson who had a gig at World Pacific Jazz. Dickson started us off when we were all broke, busted out on the street before the days of 'Any spare change?' If you said 'Any spare change?' to somebody back then, you'd get your mouth busted in. We just scuffled. Dickson supported us. One hamburger a day was our diet we got emaciated but we worked hard and everything.

We saw Michael (Clarke) on the street man, and he just looked right. David had met him up in Big Sur playing conga drums and he said, 'Hey man, you wanna be a drummer?' and Michael said, 'Sure.' so we all got together and did it.

David was originally going to be the bass player and Gene was going to be the rhythm guitarist. Well, David didn't want to learn to play the bass and Gene's timing wasn't that hot at the time he's got it together now, but his timing on the rhythm wasn't together he was a little slow on the beat. So as I said, David swiped the guitar away from Gene and we had to get a bass player so we got Chris (Hillman).

That (hiring Chris) was Dickson's idea. Dickson found Chris working at a place called Ledbetter's which is owned by Randy Sparks who started the New Christy Minstrels. Chris was playing mandolin at the time with a group called the Greengrass Group, I think. It was a horrible, watered-down, Disneyland kind of version of bluegrass. Chris was just in it for a steady $100 a week and all the beer you could drink at the club or whatever. So that was it.

Flanders: What happened to Gene Clark?

McGuinn: Well, it was a combination of things. David (Crosby) was sort of riding and hounding him. David had a better background in the English language, sciences, mathematics, and other things. He took advantage of those things to make Gene feel inferior. Gene is really an intelligent person, but he's not well educated. He's a nice guy and he's a bright cat really underneath it but he's hung up and awkward and like a country boy you know what I mean? Like he's not really a city slicker. And Crosby like took advantage of his country background, of Gene's country background, and sort of hounded him into giving up the guitar, in the beginning so David would get to play it.

David wasn't playing guitar at first Gene was. It worked for about a year-and-a-half. Gene went flying with us and everything. But one day all the pressure and a bunch of bad experiences with a chick Gene went through with after all this he had a crisis on an airplane just about to close the doors and take off for New York from LA. We were all going to do a Murry the K special. Gene flipped out on the airplane, man couldn't stand it, got off the airplane. We said, 'Hey man, if you get off the airplane, if you can't fly you can't be in the group any more.' Gene said, 'I know that, but if I stay on it I'll go crazy,' so he split.

Flanders: Why did David Crosby leave the group...

McGuinn: He was fired.

Flanders: For what reason?

McGuinn: He just wasn't making it, man. He's a great talent, you know, and a nice cat I like him you know but he was getting a little too big for his britches, you know, trying to rule the machine, you know; getting hard to work with, you know. So it was by mutual consent, you know like the three remaining Byrds got together and decided that it would be better if he wasn't around any more. (This section shows you why you have to edit an interview. This is a word-for-word transcription.) The following is how I would have edited it.

McGuinn (edited): David just wasn't making it, man. He's a great talent and a nice cat, I like him, you know but he was getting a little too big for his britches. He was trying to rule the Byrds machine and he was getting hard to work with. So it was by mutual consent. The three remaining Byrds got together and decided that it would be better if David wasn't around any more.

Flanders: What happened to Mike Clarke?

McGuinn: Well, after the big Beatlemania thing sort of faded and the girls stopped rushing the stage trying to get our clothes off and everything, or just touch us or whatever they were after I don't remember exactly what it was, something that was the gig to Michael. He's turned into a drummer, but at the time he wasn't. Like when we got him off the street he never played traps before in his life. He played conga drums and he was pretty good at it.

He's intelligent and has talent in other areas he can draw and so on. He's very good at that. But he had to learn how to play the drums and he learned cold with the Byrds. I thought he faked it pretty well I thought.

Flanders: Did you ask Mike to leave?

McGuinn: He was unhappy with it. It wasn't happening for him. He didn't dig the way things were going and it was a low point in our career. I say 'our' collectively the Byrds as an institution rather than a group of people. When Michael left it was really sort of down. The record we came out with during that point was nice (The Notorious Byrd Brothers), but it hadn't been released. That was the last record Michael was on.

Flanders: And then you got Kevin Kelly and...

McGuinn: That was Chris's cousin, see...

Flanders: Was that sort of forced on you?

McGuinn: Yeah, sort of. Chris said, 'I've got a cousin that plays drums' and, again, I wasn't very selective. I sort of trust in nature that things work out all right. I really don't try and force things together. Kevin was okay except under pressure on stage. If you had a big crowd, he'd sort of break up a little bit his timing would go bad.

Flanders: And Kevin left?

McGuinn: No. Actually he was fired another dismissal...

Flanders: ...and Gram (Parsons) was fired because he wouldn't go to South Africa?

McGuinn: Gram didn't quit, he was let go because he didn't want to go to South Africa with us (July 1968). He said he wouldn't play to segregated audiences. Actually, we went down there as a political thing to try to turn their heads around but he didn't want to participate in that, but it wasn't for political reasons. It was because he wanted to stay in London. He dug it there, dug Marianne Faithful and the Rolling Stones and he wanted to stay in that scene.

He refused to go to South Africa and his reasoning was sound from one point of view, but he didn't understand, or he was unwilling to comprehend my point of view. I'd known Miriam Makeba since I'd worked with the Mitchell Trio back in the early 1960's. Miriam was from there and she managed to escape with the help of Harry Belafonte or somebody. She told me what a horrible place it was. I knew all the political strife they were into and I wanted to go over and do what I could to help it out help the black people get liberated.

I know they're arming. I went over and told the white press over there that the blacks were getting armed. I personally knew people who were sending money over there to arm the blacks. I told them there was going to be a bloodbath unless they let up on their apartheid laws. Well, that's like going to Georgia and telling them to integrate. We got threatening letters, telegrams, phone calls in Durban.

Climatically, I enjoyed the country except I had the flu there. I got about a 103-104 degree fever. I had to work through it because we had this (pejorative term deleted) promoter from England who had hepatitis and went to South Africa to recuperate because it was summer down there when it was winter in England and vice-versa. It was winter down there and I caught the flu and they don't have heat in the hotel rooms so I would be sweating all night long and it would be 40 degrees in the room. I kept the flu about two weeks.

Flanders: Where did you find Clarence White?

McGuinn: Clarence worked on Younger Than Yesterday as a studio musician. And at the time when I first heard him I said, "Wow, man that's far out," and I wanted to hire him then but he was busy. He was with a group of his own with Gene Parsons. He was working with Gene and a couple of other guys and he worked on that project for awhile (Nashville West vf) until it didn't happen. Finally, he was available and I hired him as soon as I could. Gene Parsons came along shortly after that, right around the time Chris quit.

Now Chris didn't get fired, he quit. He got uptight one time playing his bass. He didn't want to play the bass any more so he threw it down and quit. He was my equal partner. We were 50-50 partners by that time. It went from a 5-way partnership down to a 50-50 partnership. Then Chris quit and he still hasn't legally relinquished his 50%, but technically speaking, if he went to any court, they'd throw it out because I've been working with the group and he hasn't, so he shouldn't get any of the proceeds. I went to my lawyer and got a profit-sharing system worked out so the guys in the group now are partners. I don't get 100 percent of the profit.

Flanders: About 25 percent then.

McGuinn: It's actually more at this point, but I'm still sharing with them. I'm doing administrative things as well. I'm the manager so I get a percentage for that.

Flanders: Do you do the hiring and firing yourself?

McGuinn: I'm the only one left so I do now. But at the time it was always a democratic vote thing.

Flanders: Why exactly did you go into country music?

McGuinn: Just for fun, man.

Flanders: Where are you going after? What trends are you going to follow?

McGuinn: We're not going to dump country music we're going to keep it but we're probably going to venture into electronic music.

Flanders: At the time you recorded "Sweetheart of the Rodeo" Billboard magazine said you recorded ten other tracks. When will they be released?

McGuinn: That's not true.

Flanders: You didn't record ten other tracks?

McGuinn: No.

Flanders: In other words, "Sweetheart of the Rodeo" was not supposed to be a double album, as Billboard said?

McGuinn: We said we were going to do that, but there was a change of mind in the organization so they released a country album instead.

Flanders: Since the Byrds are usually one step ahead of what's happening, do you think (going into) country music hurt you even though Sweetheart was accepted and "Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde" wasn't?

McGuinn: Possibly, I don't know. I don't think Sweetheart was that well accepted.

Flanders: It was accepted but...

McGuinn: The reason Sweetheart didn't do well was because the AM stations didn't go for country and neither did the country people, although the underground FM stations did. So we had a minority of the radio listening audience.

Flanders: So you feel that Sweetheart hurt you.

McGuinn: It hurt us financially as far as sales go.

Flanders: Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde did even worse didn't it?

McGuinn: Yeah, it did. Well, it really wasn't as good an album musically. At least Sweetheart had some integrity whereas Dr. Byrds was a more or less contrived departure. I'm not too happy with that one. That doesn't mean you should stop listening to it if you have it. An artist should never be satisfied with his own work anyway. I can't really say that I'm satisfied with anything we've ever done. I can find holes in anything we've ever done which is a healthy symptom, I think.

Flanders: What were your favorites songs off of "Dr. Byrds"?

McGuinn: I like This Wheel's On Fire and that song at the end the Jimmy Reed song called Baby What You Want Me To Do. There were a couple of other songs I really liked.

Flanders: What about the electronic music album?

McGuinn: Well, I have the Moog (synthesizer) at home. I'm working on it. It's a slow process. I'm waiting for a guitar keyboard to come out. They don't have one yet so I'm forced to play piano which I don't know how to play that's my basic hang-up about doing an electronic album.

Flanders: Will it be a Byrds album or something on Columbia Masterworks?

McGuinn: I think it should be a separate album. I want to do something really significant with it which is why I'm holding off. I like George Harrison personally I haven't seen him in a couple of years but he released an album (of electronic music) he just got his Moog and he put it all down on tape and released it right? Which I could have done too, but I'm not George Harrison.

Like what he did with it, if I'm allowed to be a critic for a minute as a Moog synthesizer musician, was something you do the first day you get it home and you try it out if you put the tape recorder on and let it roll. He went into a bunch of white noise riffs, a bunch of oscillator warble riffs things that are very simple man and really just show off the novelty gadget style it wasn't musical.

Flanders: In another magazine you said you were going to get into Jazz eventually sometime in the future. Is that...

McGuinn: ...It's possible. We like to explore different fields of music.

Flanders: I read about your musical (Gene Tryp) in Jazz and Pop and that it's going to be happening hopefully this year, right?

McGuinn: Yeah. It doesn't really matter whether it happens this year or next year, but I'd prefer to see it happen this year. It's contemporary, like country-rock oriented. It's got hard rock; it's got country. They're going to do rear projection films and slides and tapes mixed media. (It's a) McLuhanistic musical idea with a pit orchestra cause you have to have that, the union says you have to have 26 pieces at least but we want that anyway. We have a cat who's going to orchestrate the whole score. I just wrote the tunes and he's going to put it to fiddles and celli and so on.

Flanders (1969): You've had three producers in your career. Do you just change them because you don't like them or does Columbia Records say you have to work with a certain producer?

McGuinn (1969): It's actually both. We got rid of Terry Melcher for sort of internal political reasons because he was doing one thing and we wanted to do another musically. And then the second one we got [Allen Stanton] left the company to go with A&M he got a better position over there. And then we got Gary Usher, but he was fired by Columbia so we inherited Bob Johnson and I'm very happy about it. He's a gas to work with. He's beautiful

Flanders (1970): When I talked with you last year you talked about your producers you said Terry Melcher was fired for "internal political reasons" and on this last album (Ballad of Easy Rider) he's back. What's the story on that?

McGuinn (1970): I decided that he would be good to get back again because he has a great deal of know-how in the arrangement area and the A&R department. He's really good and I didn't appreciate him at the time back in the early days until we had to go through Allen Stanton. Gary Usher was good, but he got canned from Columbia. He put out an album by Chad and Jeremy called The Ark that cost $75,000 to produce and it didn't make it back. Seventy-five grand went down the drain and so did Gary Usher's career at Columbia. So he's got his own label now Together Records. I like Gary. He's a nice guy.

Flanders: What was your reaction to Preflyte which was put out by Together Records?

McGuinn: I was allowed to hear it before they put it out they needed our written permission before they could do it. I gave permission because I thought it would be an interesting historical trip. It's like a time capsule, something that was recorded like going out in the field and recording folk songs which doesn't happen any more. It's sort of in that area. If you're interested in the Byrds as an entity you want to see what they started with you can see the Beatle influences which show up much more vividly on that than they do on our first Columbia album.

Flanders: You've released some singles like Lady Friend...

McGuinn: That were never released on albums. That's because they were bombs as singles so why should we put them on albums?

Flanders: What about She Don't Care About Time?

McGuinn: I love that song, I really do. I don't know why that never got on. That was for the Turn Turn Turn album, right? I think we had enough stuff already except that I'm not too happy with the last four cuts of that album. I'm sorry about Oh Susanna. That was a joke, but it didn't come off, it was poorly told. It was a private joke between Dylan and I, actually.

I was riffing with this song we were trying to rock anything and Stephen Foster was a funny thing to rock with. Dylan said, "Yeah, you gotta do that on your next album, right?" He didn't really think I would. He didn't think I had the guts to do it so I said, "OK" and I did it. It was a bomb. As far as I was concerned it didn't come out well. We could have done it much better. If we had, it would have been funny.

Flanders: Paul Butterfield, in an article in Hit Parader magazine said that on like the first two albums or so you brought in a bass player and drummer...?

McGuinn: The first single was the only time we ever used well, we actually did use outside musicians here and there, sparsely. Clarence was used. But we did use Hal Blaine, the drummer here and there. He's a studio drummer in LA. He's on you just name a hit and he's been on it, like anybody coming out of LA. He's one of the hotter studio drummers, like all the Mamas and Papas stuff is him.

Flanders: Have you recorded any songs that haven't been put on albums? Like I remember reading an advertisement for The Notorious Byrd Brothers that said Moog Raga...

McGuinn: Yeah, we did the Moog Raga. It's in the can at Columbia, it's in the library and will never be released because it's out of tune that's the only reason. You have to stack with the synthesizer. Stacking, for those of you who don't know about what it is, it's putting one layer or channel of tape over another overdubbing. It was a stacked thing. We first put down the tambura sound, then we put down the melody line. The melody line was out of tune with the tambura sound. the 'whaangyang' sound was all right, but when we put the 'dodooyadoooyaa' I was doing it on a linear controller on the Moog. Man, it's really hard. It's like learning to play the violin immediately you play it across from right to left. Like it's horizontal and you play it by pushing your finger down on a Teflon strip about a half-inch side and about 1/5 of a millimeter in thickness and it's about one millimeter off the graphite undercoating what it is is a big potentiometer.

And so I put black grease pencil marks on the strips to find the notes, but still my ear was a little off that night is what it was. I just wasn't hearing in tune correctly the night that we did it and we never got to return to it and clean it up. Like I can do it better now from scratch because I know the synthesizer inside out electronically. My only hangup, as I say again, is the keyboard. I'm not a keyboard cat. I'm waiting for a guitar neck to come out or otherwise I have to make one myself and I'm not in town long enough to really get involved in the project it'd take six months to get a working guitar neck.

Flanders: Are they trying to make one?.

McGuinn: Paul Beaver, the west coast franchise for Moog, is allegedly trying t make one. I don't know if he will or not or how he'll work it. It's a difficult proposition because of the mechanics involved. You'd have to have switches that are small enough to put six across per fret on the guitar neck which is very small. In fact, they don't make switches that small yet. They make little buttons that small, but the switch itself is about an inch long so logistically it can't be done that way.

I had a solution in my head that I haven't proposed to anyone in the electronics field. My solution was to make a converter that would take the actual tone of the guitar through a preamp and then convert it into a voltage that would control the oscillators. It sounds good, but it would be hard to do.

Flanders (1969): What's the next single going to be?

McGuinn (1969): Lay, Lady, Lay is the title. It's a Bob Dylan Song. It's out already. It's released.

Flanders (1970): What's the next single going to be?

McGuinn: We're not sure yet, we'll have to record some more stuff. Right now it looks good for Lover of the Bayou which is a reject from my musical, Tryp not because of the musical quality, but because the scene that it was in was cut because of time. The musical ran 4 1/2 hours on the first reading so we had to cut it down to at least half of that. So the bayou scene where Gene Tryp, the main character, was in the bayou area selling guns to the Confederates and rum to the slaves. The slaves find out about it and Big Cat sings this song (Lover of the Bayou) to Gene Tryp to scare him.

That's what the story line was, but that segment's been cut out of the play. I talked to Jacques Levy three weeks ago in New York and he told me that song was clear we could use it. I've been sitting on this stuff for over a year now waiting for them to cut it.

Flanders: Any chance for Gunga Din as a single?

McGuinn: I think it's too late for that. Once you put an album out and have a single or two released off it you shouldn't go back. It would be like going back to The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Columbia Records does that sometimes without our approval. In the contract it's worded very sneakily like we have the "right of comment". It must be shown to us for our comment, but doesn't say what the hell they'll do with it after we see it.

So what usually happens is they don't even show it to us. In this last case they didn't. (Columbia put Wasn't Born to Follow as the flip side of some copies of The Ballad of Easy Rider. The original release had Oil in my Lamp.)

Flanders: (1969): What's the future album?

McGuinn: (1969): I don't know. We might do a whole album of Bob Dylan material next. It depends on the success of Lay, Lady, Lay as a single.

Flanders (1970): The next album (which turned out to be Untitled) is probably going to be the same hard rock?

McGuinn (1970): We're going to get harder rock and less country soft country.

Flanders: You never seem to have any fancy album covers. Who decides what goes on the cover and why?

McGuinn: Columbia Records is sort of a tightwad organization and they don't like to put out a lot of money for stuff like that. You can get it if you really hound them like Johnny Cash got that 3D thing on his Holy Land album. It was like the Stones' Satanic Majesties Request. You can get it if you hassle them a lot. One of these days we'll get one of those.

Flanders: Who gets to decide what goes on the albums?

McGuinn: We all decide. We consult with our A&R man that stands for Artist and Repertoire and he goes by what you're interested in, what you've got cooking, and your musical bag at the time. Sometimes he makes suggestions.

Flanders: On the Dick Cavet Show you did a version of Jesus Is Just Alright; you did another version tonight, and you did one when I saw you last year that was about 4 1/2 minutes long and had a really beautiful "McGuinn" guitar solo in it. How did the sliced-down version happen on the single?

McGuinn: The single was cut for down for time reasons because in our position we can't afford to do over 2:06. If you're the Beatles, you can go 3-4 minutes. It depends on who you are. At one point we could go three minutes. Turn, Turn, Turn was 3:35. Some stations would cut it off after the third verse they'd chop it and go into a promo or commercial. Most of them played it because at the time we were hot. Right now we're getting hotter. We're not getting any colder we can't get any colder. Like most groups would have broken up and quit by now. There's something inside me that drives me to do it. I feel that my spirit is driving me into this. I feel I'm doing a service of some kind or other.

Another person asks the following question: It may be kind of a personal question you may not want to answer...you changed your name from Jim McGuinn to Roger McGuinn. Why did you change your name?

McGuinn: I belong to an organization called Subud S-U-B-U-D and they offer an optional name change and I decided to take it. (Editor's Note: McGuinn no longer belongs to Subud, but is now a devout Christian.)

Person Interrupting: What kind of organization is it?

McGuinn: It's a spiritual organization, like Buddhism. It's an Eastern philosophy.

Flanders: Seems like I read someplace that you have a preoccupation with space and space travel and some of your songs are space oriented. Does this have to do with Subud?

McGuinn: No, not really. I'm just very technically oriented. I like the gadgets involved in space. I'm not exclusively interested in space I'm interested in the whole realm of technology.

Flanders: Who's R. J. Hippard?

McGuinn: He's a friend of mine, Bob Hippard. He and I share a fondness for science fiction and a frustration to communicate with extraterrestrial life.

Flanders: Some people took the song Mr. Spaceman about trying to communicate as a hoax.

McGuinn: Well, the song lends itself to that type of thinking because it is silly in the middle. "Blue-green footprints that glow in the dark" is a silly line and I sort of regret putting that in there, but I was trying to put out my feelings. I had just read a flying saucer book or two, or three, or four and I had just gotten into flying saucer books, testimonials highway patrol officer so-and-so was driving down highway such-and-such and he saw this orange light come in front of him and his car stopped and he got out and flashing red lights came on. Like all those books have the same reports in them basically. Some of them are real and some of them aren't. Incidentally, I'm glad they closed up Project Blue Book. Nobody's recorded any flying saucers lately, have they?

Flanders: If they are, they're not getting any press coverage.

McGuinn: It might be boycotted blackballed. It could happen.

Flanders: It seems, when you really get down to it, you are the Byrds.

McGuinn: Well, not really. Clarence White, Gene Parsons, and Skip Battin should not be discounted. You can't say that about them and not discount them. So you have to say I started the Byrds and that I sustained them, but the contributions are made by the other guys in the group are very strong and worthy of comment. Too many people jump to the conclusion that the Byrds would be the same no matter who else was in it besides me. I never wanted to have it that way.

Flanders: The Byrds have sort of a constant sound but changing at the same time.

McGuinn: Yeah. That's been part of our fun. We knew about getting locked into a bag like so many groups did. They had success for a while and they were locked into their bag and their bag just fell down and they fell down with it. Like we would do a Houdini from every bag that we got locked into with handcuffs on. We'd pick the locks and jump out of the bag. Tah Dah! Here we are in the country field; here we are in the rock field; here we are in the jazz field we're doing a number on the public which they didn't really take too well, but at least we didn't get locked into a bag. We're not folk-rock you can't say that about us any more, really. We do it. We do the old stuff as well or better than the original group did live. Right?

Flanders: The last time you were here (Indianapolis, Indiana, 1966) a cherry bomb was thrown at you.

McGuinn: Really? I don't remember.

Flanders: You did about 15 minutes and a cherry bomb was thrown at you and you split.

McGuinn: I like cherry bombs. I throw them myself but not at people. I didn't take it like they were throwing them at me. I have no mental record of it I may have repressed it.

Flanders: Gene (Clark) had just left when you were here...

McGuinn: Ah! 'Where's Gene?' I remember that. People saying, 'Where's Gene?' like greasers 'WHERE'S GENE?' Well, he got uptight on the airplane...

Flanders: Do you think you'll ever get back the popularity you once had?

McGuinn: Yeah. I can't guarantee it, but I know one fact about show business. Take Sinatra. He was down for 7 years and then he came up bigger than ever. If you keep plugging away at it and if you love it I just saw Jimmy Durante, he just had a birthday the other day and he wouldn't divulge his age, but he's in his late 70's right? And they asked, "Why do you stay in the business so long?" and he said, "Because I love it." And that's my answer I love it. I have this passionate love for the music business and show business in general.

Flanders: Are you going to be a musician forever?

McGuinn: Yeah. Whether I'm doing it professionally or at home I'll never stop being a musician. I mean, there's no way of getting out of being a musician. Once you learn how to play, you're hooked on it. It's like drugs or something it's like coffee or cigarettes. Music is really a great release for your emotions.

________________________________________________

Only after the last tree has been cut down,

Only after the last river has been poisoned,

Only after the last fish has been caught,

Only then will you find money cannot be eaten.

~ Cree Prophecy |

| 8 L A T E S T R E P L I E S (Newest First) |

| rocker |

Posted - 27/09/2012 : 14:30:06

Right now I'm looking to get the other lps in mono. I think a Japan Sony pressing has them.

And just an fyi....I read that there's a kind of massive lp renaissance going on in Japan where collectors are on the hunt for obscure pop records done here in the States by artists who unfortunately have been relegated to the backwater of musical time. they didn't make it but there lps still are found in dusty attics , chests and trunks. Japanese collectors going for that sweet, sugary pop sound that we had a generation ago. hehehh they love Pattie Pages' 'Doggie in the Window'!!!!.... |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 26/09/2012 : 16:14:49

quote:

Originally posted by rocker

But then if you are a fan, you love them all! And the expanded editions of those two do stand up far better than the original LPs did.

Yes, like most of us yes we're fans of all. We have our preferences and mine is when they play that 12 string 'jingle jangle' sound thanks to John Paul George Ringo. (there they are again!) Sublime stuff. Last week I managed to get a copy of the Byrds 'Turn Turn Turn' record on mono. (lk man really it's because of you that I'm selling couches to get those records!) Took it home, and like Procul Harum..hey me and my "ceiling blew away"...

Glad you found that mono Turn Turn Turn LP, rocker....sweet, huh?!! The mono is really great.

One of the finest mono mixes ever is Younger Than Yesterday...get it when you can.

________________________________________________

Only after the last tree has been cut down,

Only after the last river has been poisoned,

Only after the last fish has been caught,

Only then will you find money cannot be eaten.

~ Cree Prophecy |

| rocker |

Posted - 26/09/2012 : 14:51:47

Buglar....great song..beautiful stuff..I can smell that countrified aire... . .

I've been thinking. I have been listening to two songs for almost my whole life. Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn Turn Turn. I know every note and musical 'cranny' in them. Some songs stick with us "forever and through changes", eh? I'm sure you all have ones you will ALWAYS ALWAYS listen to. |

| John9 |

Posted - 21/09/2012 : 09:16:45

Yes Rocker - the jingle jangle albums are the definitive ones......and I would say that those are Mr Tambourine Man, Turn! Turn! Turn!, Fifth Dimension, Younger Than Yesterday and The Notorious Brothers. I suppose that to some extent that sound is back on Chestnut Mare....but it is those first five that to my mind make The Byrds the most important American group ever. But I for one am glad that McGuinn kept things going after 1967. Sweetheart of the Rodeo was uniquely influential......and of course the 'Clarence White Byrds' were responsible for some excellent tracks. Here's a favourite of mine from the very end:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q36cCm3OMbI

That mono single of yours.......I first heard it in late 1965 on BBC's Juke Box Jury....and then a couple of nights later on Radio Luxembourg. I thought that it was the best thing I had ever heard in my life. We are so lucky to have lived through all that. |

| rocker |

Posted - 20/09/2012 : 22:34:24

But then if you are a fan, you love them all! And the expanded editions of those two do stand up far better than the original LPs did.

Yes, like most of us yes we're fans of all. We have our preferences and mine is when they play that 12 string 'jingle jangle' sound thanks to John Paul George Ringo. (there they are again!) Sublime stuff. Last week I managed to get a copy of the Byrds 'Turn Turn Turn' record on mono. (lk man really it's because of you that I'm selling couches to get those records!) Took it home, and like Procul Harum..hey me and my "ceiling blew away"... |

| John9 |

Posted - 20/09/2012 : 20:52:09

Thanks once again, LK - great interview. As I think you know, Untitled has always been a favourite of mine too...in fact it was, being their current album in early '71, the first one I bought. I think that after that one they spent so much time touring that they scarcely had time to write. It is this perhaps that helps to explain the mediocrity of their final two albums.....Byrdmaniax and Farther Along. But then if you are a fan, you love them all! And the expanded editions of those two do stand up far better than the original LPs did. |

| lemonade kid |

Posted - 20/09/2012 : 17:39:00

True words, Rocker.

This interview led me to go to "later" works...right now "(Untitled)".

"Chestnut Mare"....beautiful fantasy cowboy song. "Truckstop Girl"..."All The Things"..."Yesterday's Train" sounds like a Gene Clark tune might be handled here.

Great album. Roger is a legend and so glad he really did, AND DOES, keep the music going.

Too bad we Roger never realized the musical "Gene Tryp", though four songs here are from the imagined musical.

A fine album indeed.

Roger finally got to work in the MOOG on "Hungry Planet", as he hoped he could someday (in the interview)

............................

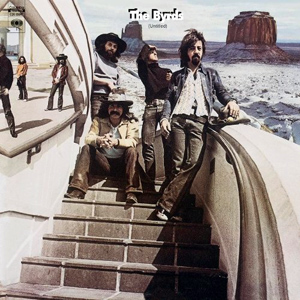

Untitled (The Byrds album)

Truck Stop Girl

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jRBKcrn9Xlk&feature=related

(Untitled) is the ninth album by the American rock band The Byrds and was released in September 1970 on Columbia Records (see 1970 in music).[1] It is a double album, with the first LP featuring live concert recordings from two early 1970 performances in New York City and with the second LP consisting of new studio recordings.[2] The album represented the first official release of any live recordings by the band as well as the first appearance on a Byrds' record of new recruit Skip Battin, who had replaced the band's previous bass player, John York, in late 1969.[3][4]

The studio album mostly consisted of newly written, self-penned material, including a number of songs that had been composed by band leader Roger McGuinn and Broadway theatre director Jacques Levy for a planned country rock musical that the pair were developing.[4] The production was to have been based on Henrik Ibsen's Peer Gynt and staged under the title of Gene Tryp (an anagram of Ibsen's play), with the narrative taking place in the south-west of America during the mid-19th century.[5] However, plans for the musical fell through and five of the songs that had been intended for Gene Tryp were instead recorded by The Byrds for (Untitled)although only four appeared in the album's final running order.[4]

The album peaked at #40 on the Billboard Top LPs chart and reached #11 on the UK Albums Chart.[6][7] A single taken from the album, "Chestnut Mare" b/w "Just a Season", was released in the U.S. in October 1970 but missed the Billboard Hot 100 chart, bubbling under at #121.[1] The single was later released in the UK in January 1971, where it did considerably better, reaching #19 on the UK Singles Chart.[1][7] Upon release, (Untitled) was met with positive reviews and strong sales, with many critics and fans regarding the album as a return to form for the band.[2] Likewise, the album is today generally regarded as being the best that the latter-day line-up of The Byrds produced.[9]

Following the firing of The Byrds' bass player, John York, in September 1969, Skip Battin was recruited as a replacement at the suggestion of drummer Gene Parsons and guitarist Clarence White.[10][11] Battin was, at 35, the oldest member of the band and the one with the longest musical history.[11] Battin's professional career in music had begun in 1959, as one half of the pop music duo Skip & Flip.[4] The duo had notched up a string of hits between 1959 and 1961, including "It Was I", "Fancy Nancy", and "Cherry Pie".[12] After the break-up of Skip & Flip, Battin moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a freelance session musician and formed the band Evergreen Blueshoes.[4] Following the disbandment of that group, Battin returned to session work in the late 1960s and it was during this period that he met Gene Parsons and became reacquainted with Clarence White, whom he had known from a few years earlier.[11] York's dismissal and Battin's recruitment marked the last line-up change to The Byrds for almost three years, until Parsons was fired by McGuinn in July 1972.[13] Thus, the McGuinn, White, Parsons, and Battin line-up of the band was the most stable and longest lived of any configuration of The Byrds.[4][14]

For most of 1969, The Byrds' leader and guitarist, Roger McGuinn, had been developing a country rock stage production of Henrik Ibsen's Peer Gynt with former psychologist and Broadway impresario Jacques Levy.[15] The musical was to be titled Gene Tryp, an anagram of the title of Ibsen's play, and would loosely follow the storyline of Peer Gynt with some modifications to transpose the action from Norway to south-west America during the mid-19th century.[5] The musical was intended as a prelude to even loftier plans of McGuinn's to produce a science-fiction film, tentatively titled Ecology 70 and starring former Byrd Gram Parsons (no relation to Gene) and ex-member of The Mamas & the Papas, Michelle Phillips, as a pair of intergalactic flower children.[11] Ultimately, Gene Tryp was abandoned and a handful of the songs that McGuinn and Levy had written for the project would instead see release on (Untitled) and its follow-up, Byrdmaniax.[4]

Of the twenty-six songs that were written for the musical, "Chestnut Mare", "Lover of the Bayou", "All the Things", and "Just a Season" were included on (Untitled), while "Kathleen's Song" and "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician" were held over for The Byrds' next album.[9][16][17] "Lover of the Bayou" would later be re-recorded by Roger McGuinn in 1975 and appear on his Roger McGuinn & Band album.[18] Despite not being staged at the time, Gene Tryp was eventually performed in a revised configuration by the drama students of Colgate University between November 18 and November 21, 1992, under the new title of Just a Season: A Romance of the Old West.[19][20][21]

[edit] Conception and title

Having toured extensively throughout 1969 and early 1970, The Byrds decided that the time was right to issue a live album.[2][3] At the same time, it was felt that the band had a sufficient backlog of new compositions to warrant the recording of a new studio album.[2] The dilemma was resolved when it was suggested by producer Terry Melcher that the band should release a double album, featuring an LP of concert recordings and an LP of new studio recordings, which would retail for the same price as a regular single album.[2] At around this same time, the band's original manager Jim Dickson, who had been fired by the group in June 1967, returned to The Byrds' camp to help Melcher with the editing of the live recordings, affording him a co-producers credit on (Untitled).[22]

The album's innominate title actually came about by accident.[2] According to Jim Bickhart's liner notes on the original double album sleeve, the group's intention was to name the release something more grandiose, such as Phoenix or The Byrds' First Album.[23] These working titles were intended to signify the artistic rebirth that the band felt the album represented.[3] Another proposed title for the album was McGuinn, White, Parsons and Battin but McGuinn felt that this title might be misinterpreted by the public.[2] The band still had not made up their minds regarding a title when Melcher, while filling out record company documentation for the album sessions, wrote the placeholder "(Untitled)" in a box specifying the album's title.[2] A misunderstanding ensued and before anyone associated with the band had realized, Columbia Records had pressed up the album with that title, including the parentheses.[14]

Live recordings

The latter-day line-up of The Byrds, featuring McGuinn, White, Parsons, and Battin, was regarded by critics and audiences as being much more accomplished in concert than previous configurations of The Byrds had been.[24] This being the case, it made perfect sense to capture the band's sound in a live environment and so, in February and March 1970, two consecutive New York concert appearances were recorded.[2][25] The first of these was the band's performance at the Colden Center Auditorium, Queens College on February 28, 1970, with the second being their performance at the Felt Forum on March 1, 1970.[4][25] (Untitled) featured recordings from both of these concerts, spliced together to give the impression of a single continuous performance.[26] Of the seven live tracks featured on the album, "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", "Mr. Tambourine Man", "Mr. Spaceman", and "Eight Miles High" were drawn from the Queens College performance, while "Lover of the Bayou", "Positively 4th Street", and "Nashville West" originated from the Felt Forum show.[27][28][29] The appearance on the live LP of the band's earlier hit singles "Mr. Tambourine Man", "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", and "Eight Miles High" had the effect of forging a spiritual and musical link between The Byrds' current line-up and the original mid-1960s incarnation of the band.[3]

The opening track of the live LP is "Lover of the Bayou", a new song written by McGuinn and Levy for their aborted Gene Tryp stage show.[3] The song is set during the American Civil War and was intended for a scene in which the eponymous hero of the musical is working as a smuggler, bootlegger, and gun runner for both the Confederacy and the Unionists.[3] Despite the central character's appearance in the scene, McGuinn explained in a 1970 interview with journalist Vincent Flanders that the song wasn't actually intended to be sung by Gene Tryp but by another character, a voodoo witch-doctor (or houngan) named Big Cat.[30][31] "Lover of the Bayou" is followed on the album by a cover of Bob Dylan's "Positively 4th Street", which would be the last Dylan song that The Byrds would cover on an album until "Paths of Victory", which was recorded during the 1990 reunion sessions featured on The Byrds box set.[3] The remainder of side one of (Untitled) is made up of live versions of album tracks and earlier hits.[4] In a 1999 interview with journalist David Fricke, McGuinn explained the rationale behind the inclusion of earlier Byrds' material on the album: "The live album was Melcher's way of repackaging some of the hits in a viable way. Actually, I wanted the studio stuff to come first. Terry wouldn't hear of it."[4]

Side two of the live album is taken up in its entirety by a sixteen minute, extended version of "Eight Miles High",[16] which proved to be popular on progressive rock radio during the early 1970s. The track is highlighted by the dramatic guitar interplay between McGuinn and White as well as the intricate bass and drum playing of Battin and Parsons.[9][16] The song begins with improvisational jamming, which lasts for over twelve minutes and culminates in an iteration of the song's first verse.[16][31] The Byrds' biographer, Johnny Rogan, has noted that the revamping of "Eight Miles High" featured on (Untitled) represented the ultimate fusion of the original Byrds and the newer line-up.[16] At the end of the live performance of "Eight Miles High", the band can be heard playing a rendition of their signature stage tune "Hold It", which had first been heard on record at the close of the "My Back Pages/B.J. Blues/Baby What You Want Me to Do" medley included on Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde.[16]

Additional live material from The Byrds' early 1970 appearances at Queens College and the Felt Forum has been officially released over the years. "Lover of the Bayou", "Black Mountain Rag (Soldier's Joy)", and a cover of Lowell George's "Willin'", taken from the Queens College concert, were included on The Byrds box set in 1990.[28] Additionally, performances of "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", "Old Blue", "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)", "Ballad of Easy Rider", "My Back Pages", and "This Wheel's on Fire" from the Felt Forum show were included on the expanded (Untitled)/(Unissued) release in 2000.[3] A further two songs, "You All Look Alike" and "Nashville West", taken from the Queen's College concert were included on the 2006 box set There Is a Season.[29]

[edit] Studio recordings

The studio recording sessions for (Untitled) were produced by Terry Melcher and took place between May 26 and June 11, 1970 at Columbia Studios in Hollywood, California.[26][27] Melcher had been the producer of The Byrds' first two albums in 1965, Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn!, as well as producer of their previous LP, Ballad of Easy Rider.[32] The majority of the songs included on the studio album were penned by the band members themselves, in stark contrast to their previous album, which had largely consisted of cover versions or renditions of traditional material.[33]

Among the songs recorded for the album were Parsons and Battin's "Yesterday's Train", a gentle meditation on the theme of reincarnation; a cover of Lowell George and Bill Payne's "Truck Stop Girl", sung by Clarence White; and a light-hearted reading of Lead Belly's "Take a Whiff on Me".[3][34] The album also included the Battin-penned "Well Come Back Home", a heartfelt comment on the Vietnam War.[4] Battin explained the song's genesis to author Johnny Rogan during a 1979 interview: "I was personally touched by the Vietnam situation, and my feelings about it came out in that song. I had a high school friend who died out there and I guess my thoughts were on him at the time."[16] Battin also revealed in the same interview that he couldn't decide whether to name the song "Well Come Back Home" or "Welcome Back Home" but finally settled on the former.[16] Curiously, although the song was listed on the original album and the original CD issue of (Untitled) as "Well Come Back Home", it was listed as "Welcome Back Home" on the (Untitled)/(Unissued) re-release in 2000, possibly in error.[3] With a running time of 7:40, the song is the longest studio recording in The Byrds' entire oeuvre.[26] In addition, the song also continues the tradition of ending The Byrds' albums on an unusual note, with Battin chanting the Buddhist mantra "Nam Myoho Renge Kyo" towards the end of the song.[3]

"Chestnut Mare" had originally been written during 1969 for the abandoned Gene Tryp stage production.[5] The song was intended to be used in a scene where Gene Tryp attempts to catch and tame a wild horse, a scene that had originally featured a deer in Ibsen's Peer Gynt.[16] Although the majority of "Chestnut Mare" had been written specifically for Gene Tryp, the lilting Bach-like middle section had actually been written by McGuinn back in the early 1960s, while on tour in South America as a member of the Chad Mitchell Trio.[3] Two other songs originally intended for Gene Tryp were also included on the studio half of (Untitled): "All the Things", which included an uncredited appearance by former Byrd Gram Parsons on backing vocals, and "Just a Season", which was written for a scene in which the eponymous hero of the musical circumnavigates the globe.[16][35] Lyrically, "Just a Season" touches on a variety of different subjects, including reincarnation, life's journey, fleeting romantic encounters and finally, stardom, as touchingly illustrated by the semi-autobiographical line "It really wasn't hard to be a star."[36][37]

The album also includes the song "Hungry Planet", which was written by Battin and record producer, songwriter, and impresario Kim Fowley.[16] The song is one of two BattinFowley collaborations included on (Untitled) and features a lead vocal performance by McGuinn.[26][31] The ecological theme present in the song's lyrics appealed to McGuinn, who received a co-writing credit after he completely restructured its melody prior to recording.[16] Journalist Matthew Greenwald, writing for the Allmusic website, has noted that "Hungry Planet" has an underlying psychedelic atmosphere which is enhanced by the sound of the Moog modular synthesizer (played by McGuinn) and the addition of earthquake sound effects.[3][38] The album's second BattinFowley penned song, "You All Look Alike", was again sung by McGuinn and provided a sardonic view of the plight of the hippie in American society.[3][26]

Six songs that were attempted during the (Untitled) recording sessions were not present in the album's final running order. Of these, "Kathleen's Song" would be held over until Byrdmaniax, a cover of Dylan's "Just Like a Woman" would not be issued until the release of The Byrds box set in 1990, and "Willin'" would be issued as a bonus track on the (Untitled)/(Unissued) re-release in 2000.[17][31] Additionally, an improvised jam was recorded during the album sessions and was logged in the Columbia files under the title of "Fifteen Minute Jam".[28] Two different excerpts from this jam were later issued on The Byrds box set and (Untitled)/(Unissued), where they were given the retronyms of "White's Lightning Pt.1" and "White's Lightning Pt.2" respectively.[3][28] Two other songs attempted in the studio but not included on (Untitled) were John Newton's Christian hymn "Amazing Grace", which was originally intended to be the final track on the album, and a cover of Dylan's "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)".[31][39] As of 2012, neither of these two songs have been officially released in their studio configuration, although live versions are included on (Untitled)/(Unissued), with "Amazing Grace" appearing as a hidden track.[40] "Lover of the Bayou" was also recorded during studio sessions for (Untitled) but ultimately, a live recording of the song would be included on the album instead, with the studio recording appearing for the first time on (Untitled)/(Unissued).[26][40]

Release

(Untitled) was released on September 14, 1970 in the United States (catalogue item G 30127) and November 13, 1970 in the United Kingdom (catalogue item S 64095).[1] Despite being a double album release, (Untitled) retailed at a price similar to that of a single album, in an attempt to provide value for money and increase sales. Although the album was released exclusively in stereo commercially, there is some evidence to suggest that mono copies of the album (possibly radio station promos) were distributed in the U.S.[1][41] In addition, there are advance promo copies of (Untitled) known to exist which list both "Kathleen's Song" and "Hold It" as being on the album: the former under the simplified title of "Kathleen" and the latter as "Tag".[42][43] While "Hold It" does indeed appear on the official album release, at the end of the live recording of "Eight Miles High", it was not listed as a separate track on commercially released copies of the album.[1][16] "Kathleen's Song", however, was not included in the album's final running order.[9]

The album peaked at #40 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, during a chart stay of twenty-one weeks, and reached #11 in the United Kingdom, spending a total of four weeks on the UK charts.[7][44] The "Chestnut Mare" single was released some weeks after the album on October 23, 1970 and bubbled under at #121 on the Billboard singles chart. The single fared better when it was released in the UK on January 1, 1971, reaching #19 on the UK Singles Chart, during a chart stay of eight weeks.[1][7] (Untitled) is the only double album to be released by The Byrds (excluding later compilations) and is therefore the band's longest album by far. In fact, the studio LP alone, which has a running time of roughly 38 minutes, is longer than any other Byrds albumdespite containing fewer tracks than any of the band's other albums.

The album cover artwork was designed by Eve Babitz and featured photographs taken by Nancy Chester of The Byrds upon the steps of Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, with the view of L.A. that originally made up the background being replaced by a desert scene.[26][31] When the double album gatefold sleeve was opened up, the front and back cover photographs were mirrored symmetrically in a style reminiscent of the work of graphic artist M. C. Escher. The inside gatefold sleeve featured four individual black & white photographic portraits of the band members, along with liner notes written by Jim Bickhart and Derek Taylor.

Reception

Review scores

Allmusic 4/5 stars [6]

Robert Christgau C+ [45]...of course, Robert gives a lower score than is widely felt.

Blender 3/5 stars [46]

Upon its release, (Untitled) was met with almost universal critical acclaim and strong international sales, with advance orders alone accounting for the sale of 100,000 copies.[2] The album's success continued the revival of the band's commercial fortunes that had begun with the release of their previous album, Ballad of Easy Rider.[31] Many fans at the time regarded the album as a return to greatness for the band and this opinion was echoed by many journalists.[2] Bud Scoppa, writing in the November 16, 1970 edition of Rock magazine, described the album as "easily their best recorded performance so far - in its own class as much as the records of the old Byrds were - and I think one of the best half-dozen albums of 1970." Ben Edmonds' review in the December issue of Fusion magazine was also full of praise: "(Untitled) is a joyous re-affirmation of life; it is the story of a band reborn. The Byrds continue to grow musically and lead stylistically, but they do so with an unailing sense of their past." Edmonds concluded his review by noting that "History will no doubt bear out the significance of The Byrds' contribution to American popular music, but, for the time being, such speculations are worthless because (Untitled) says that The Byrds will be making their distinctive contributions for quite some time to come."

Another contemporary review by Bruce Harris, published in Jazz & Pop magazine, declared that the album "brings The Byrds back as the super cosmic-cowboys of all time, and is without question their greatest achievement since The Notorious Byrd Brothers." However, Lester Bangs was less enthusiastic about the album in his review for Rolling Stone magazine: "This double album set is probably the most perplexing album The Byrds have ever made. Some of it is fantastic and some is very poor or seemingly indifferent (which is worse), and between the stuff that will rank with their best and the born outtakes lies a lot of rather watery music, which is hard to find much fault with but still harder for even a diehard Byrds freak to work up any enthusiasm about."

In the UK, Disc magazine awarded (Untitled) a top rating of four stars, commenting "[This] is probably the most intelligent collection of songs ever assembled on a double LP... The Byrds show they retain all their imagination yet at the same time retain their unique sound."[47] Roy Carr, writing in the NME, noted that "The Byrds still retain an artistry and freshness unmatched by most others in their genius. Even changes in personnel and direction haven't dulled their appeal or magical charms."[47] Yet another complementary review came from the pen of Richard Williams, who described The Byrds' new album as "simply their most satisfying work to date" in his review for the Melody Maker.[47]

Today, (Untitled) is generally considered by fans and critics to be The Byrds' best latter-day album.[9] In his review for the Allmusic website, Bruce Eder attempted to evaluate the album's significance within the context of The Byrds' back catalogue: "listening to this album nearly 40 years later, it now seems as though this is the place where the latter-day version of the group finally justified itself as something more important than just a continuation of the mid-'60s band."[9] In his 2000 review for The Austin Chronicle, Raoul Hernandez gave the album a rating of four stars out of five, describing it as "beginning with a biting live set before giving way to a studio side of crackling Americana fare."[48] However, renowned rock critic Robert Christgau was disparaging of the album in a review published on his website: "The songs are unworthy except for the anomalous McGuinn showcase "Chestnut Mare," the harmonies are faint or totally absent, and the live performance that comprises half this two-record set...well, I'm sure you had to be there."[45]

(Untitled) was remastered at 20-bit resolution as part of the Columbia/Legacy Byrds series. It was reissued in an expanded form with the new title of (Untitled)/(Unissued) on February 22, 2000. The remastered reissue of the album contains an entire bonus CD of previously unreleased live and studio material from the period.[40] The six studio based bonus tracks on the reissue include alternate versions of "All the Things", "Yesterday's Train", and "Lover of the Bayou", along with the outtake "Kathleen's Song".[3] The remaining eight bonus tracks are live recordings taken from The Byrds' concerts on March 1, 1970 at the Felt Forum and September 23, 1970 at the Fillmore East.[3]

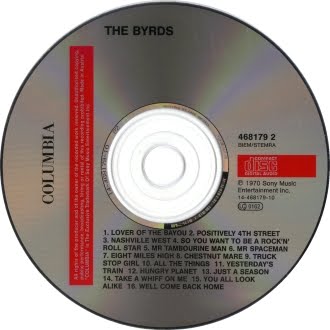

Track listing

Side 1 (live)

1. "Lover of the Bayou" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 3:39

2. "Positively 4th Street" (Bob Dylan) 3:03

3. "Nashville West" (Gene Parsons, Clarence White) 2:07

4. "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star" (Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman) 2:38

5. "Mr. Tambourine Man" (Bob Dylan) 2:14

6. "Mr. Spaceman" (Roger McGuinn) 3:07

Side 2 (live)

1. "Eight Miles High" (Gene Clark, Roger McGuinn, David Crosby) 16:03

Side 3 (studio)

1. "Chestnut Mare" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 5:08

2. "Truck Stop Girl" (Lowell George, Bill Payne) 3:20

3. "All the Things" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 3:03

4. "Yesterday's Train" (Gene Parsons, Skip Battin) 3:31

5. "Hungry Planet" (Skip Battin, Kim Fowley, Roger McGuinn) 4:50

Side 4 (studio)

1. "Just a Season" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 3:50

2. "Take a Whiff on Me" (Huddie Ledbetter, John Lomax, Alan Lomax) 3:24

3. "You All Look Alike" (Skip Battin, Kim Fowley) 3:03

4. "Well Come Back Home" (Skip Battin) 7:40

2000 CD reissue bonus tracks

1. "All the Things" [Alternate Version] (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 4:56

2. "Yesterday's Train" [Alternate Version] (Gene Parsons, Skip Battin) 4:10

3. "Lover of the Bayou" [Studio Recording] (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 5:13

4. "Kathleen's Song" [Alternate Version] (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) 2:34

5. "White's Lightning Pt.2" (Roger McGuinn, Clarence White) 2:21

6. "Willin'" [Studio Recording] (Lowell George) 3:28

7. "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" [Live Recording] (Bob Dylan) 2:56

8. "Old Blue" [Live Recording] (traditional, arranged Roger McGuinn) 3:30

9. "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" [Live Recording] (Bob Dylan) 2:49

10. "Ballad of Easy Rider" [Live Recording] (Roger McGuinn) 2:22

11. "My Back Pages" [Live Recording] (Bob Dylan) 2:41

12. "Take a Whiff on Me" [Live Recording] (Huddie Ledbetter, John Lomax, Alan Lomax) 2:45

13. "Jesus Is Just Alright" [Live Recording] (Arthur Reynolds) 3:09

14. "This Wheel's on Fire" [Live Recording] (Bob Dylan, Rick Danko) 6:16

* NOTE: this song ends at 5:08; at 5:17 begins "Amazing Grace" (traditional, arranged Roger McGuinn, Clarence White, Gene Parsons, Skip Battin)

Personnel

The Byrds

* Roger McGuinn - guitar, Moog synthesizer, vocals

* Clarence White - guitar, mandolin, vocals

* Skip Battin - electric bass, vocals

* Gene Parsons - drums, guitar, harmonica, vocals

Chestnut Mare

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUbxEu-qY0s

________________________________________________

Only after the last tree has been cut down,

Only after the last river has been poisoned,

Only after the last fish has been caught,

Only then will you find money cannot be eaten.

~ Cree Prophecy |

| rocker |

Posted - 20/09/2012 : 14:20:34

Good info..jam-packed....I found it interesting to see that both groups the Beatles and Byrds had internal squabbles but the difference was the Beatles stuck it out together until they managed to go out as "one" not in drips and drabs like McGuinn and company. Just as an opinion: I don't think there is a real bad record with the Beatles nor with the Byrds but with the latter arguably some of their work as "The Byrds" isn't up to snuff at times. That constant change of personnel was a cause of that I think. Looking back to the Beatles it would be weird to see different guys going in and out of the group. Really the Beatles even with all the strife between personalities were tight and the music did not suffer. No matter what they just couldn't bring in 'strangers'. |

|

|